Temperatures are rising, and bass are transitioning into their summer patterns. Looking for a cool tip on scoring a hot bite? Pull up a chair and listen to what these Bassmaster Elite Series anglers have to say.

Editor’s note: Land of Giants Fall | Winter | Summer | Spring

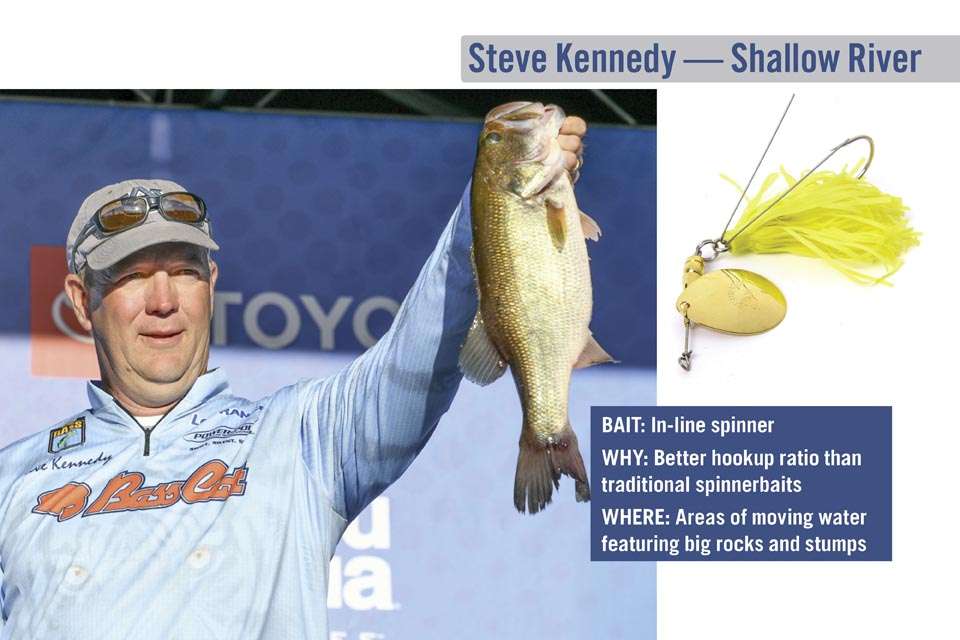

Steve Kennedy

A man of tradition, Kennedy’s going old school in his summer giant pursuit. His choice: a 1/2-ounce yellow/black Hildebrandt Snagless Sally in-line spinner — a bait that proves more efficient than a more common shallow-cover option.

“I try to avoid a typical spinnerbait because when a big fish hits it, he gets the blades and all, and I seem to miss too many bites on it,” Kennedy said. “This is something my dad picked up down at the St. Johns River 50 years ago, and in shallow, muddy water, it catches big ones.”

Favoring a size 4 1/2 blade for head-turning thump, Kennedy generally removes the weedguards for even better hookups and adds a green/white pork frog trailer. He’s stashed away several jars of the swine skin, but if you’re having trouble finding these trailers, Kennedy points to a NetBait Paca Craw as a suitable option.

Acknowledging that the bladed jig era has largely overshadowed this throwback bait, Kennedy says a little retro has a way of standing out in the sea of sameness. Moreover, his vintage bait presents a more enticing profile.

“This is a similar presentation as the [bladed jig], but I haven’t found one that’s as big as the Snagless Sally,” Kennedy said. “Maybe it’s the length, I don’t know what it is, but this bait just gets bigger bites and I can catch ’em.

“This bait’s designed for fishing in grass, pads, that type of stuff [with weedguard intact], and it’s really popular in tidal fisheries, but I like it anytime you have moving water with big rocks and stumps, which position the fish so you can target them. It’s hard to throw a big bait like that all day long. It’s not like you’re going to catch 10 on it in one spot — you’re hunting for big fish.”

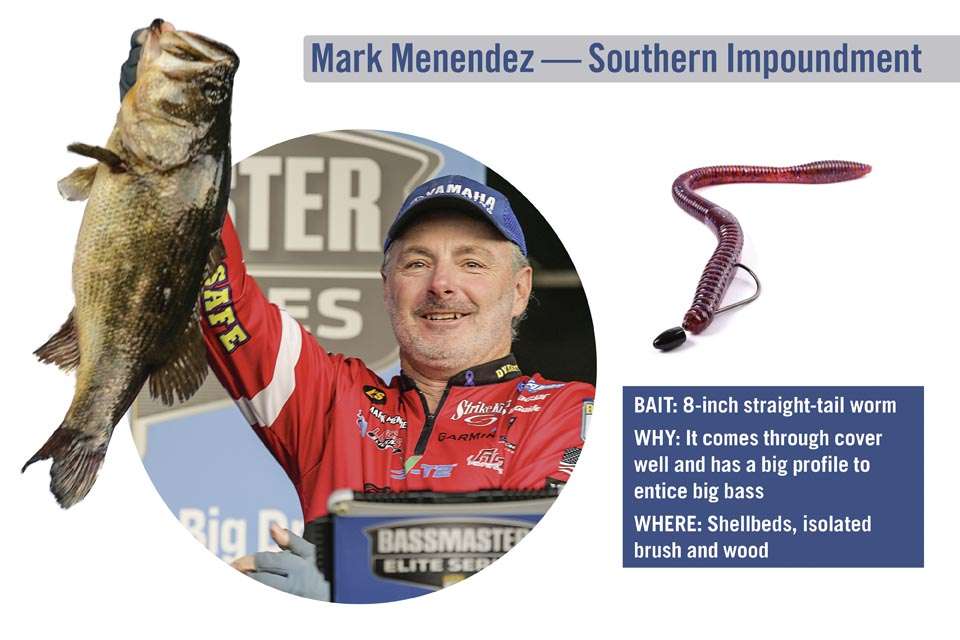

Mark Menendez

Menendez’s big-bite strategy starts with a beefy 8-inch Strike King Bull Worm (plum) rigged on a 6/0 flipping hook, capped with a 1/2-ounce Strike King Tour Grade tungsten sinker and fished on a 7 1/2-foot Lew’s flipping stick with a Lew’s 7.5:1 Hyper Mag reel carrying 15-pound Seaguar fluorocarbon. What happens next is straight-up home invasion, but he’s targeting bass, so that makes it OK.

“First, I want to be on a shellbed where current is washing across it and bass are gathering on that shellbed because it’s hard,” Menendez said. “I’m dragging the bait or using really light hops to get those grouped-up fish going. June water temperatures are going to range from 72 to 82 [degrees], so the hotter the water, the less rod movement.

“When the water is hot, I try to find what I call ‘a condominium’ — a big stump, a washed-in log, a brushpile in 12 to 25 feet — and then I penetrate it. I get that worm inside and I lift it up 6 inches and I set it down. Then I lift it up 6 inches and I set it down. You’ll lift it up 6 inches one time and it only falls 3 inches. Well, you just got bit.”

As Menendez notes, the big worm’s no one-trick pony. In fact, he’ll often give his offshore fish a breather while he runs up the reservoir to target shallow condos on river flats. He’ll use the same setup, with a 5/16-ounce sinker, and pitch it to isolated wood.

“That is a deadly way of catching some really big bass on the Cumberland or the Tennessee River that time of year,” Menendez said. “Those fish get positioned on that cover after a shad spawn. You’d think they’d want something small, like those 3/4-inch shad, but you put that big worm in there and when you get a bite, it’s one that really counts.”

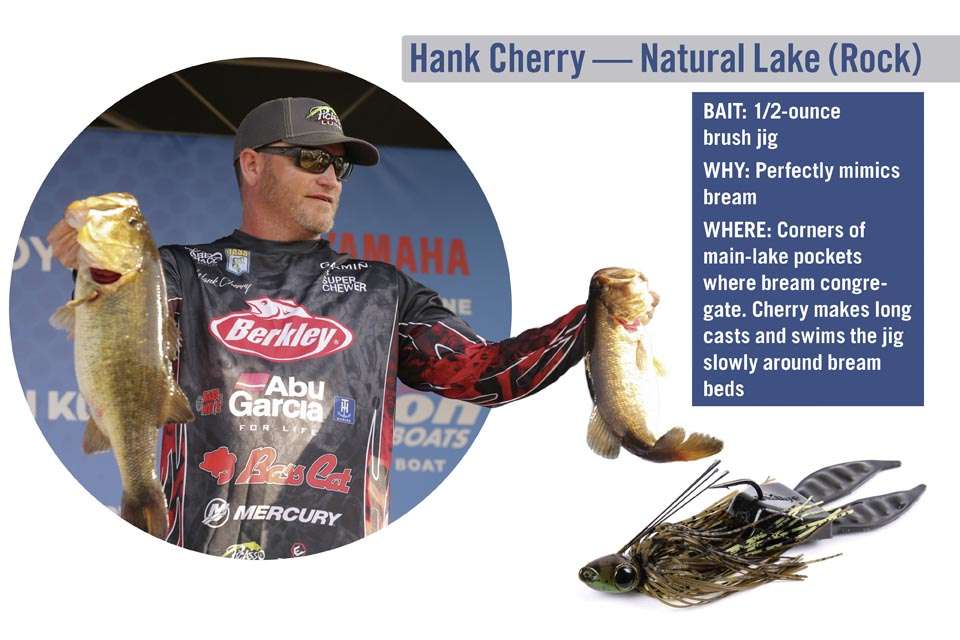

Hank Cherry

Cherry’s more than capable of handling his own business, but when he’s looking for a big-time bite, he won’t hesitate to leverage someone else’s effort — specifically, the bass magnets known as bream beds. Knowing that it takes a real giant to gobble one of these hand-sized panfish, the North Carolina pro’s going to swim an oversized jig through the area to show wolf pack bass a hefty profile that mimics what they’re targeting.

Cherry likes his 1/2-ounce signature series Picasso Straight Shooter brush jig, as its conical head design and recessed, straight line tie give it great swimming dynamics. He’ll pair this with a swimbait trailer or a 3.25-inch Berkley Power Chunk, depending on the scenario.

“I’d go with the swimbait when the fish are active and the lake doesn’t have as much pressure,” Cherry notes. “If I went with the chunk, it would be less subtle, but I could swim it slower … and a lot of times you get a bigger bite with that style of bait.

“As far as colors, it would be the green pumpkins and the browns [to match the bream]. But every now and then, you run into a late shad spawn — then you’d throw a white one.”

Cherry said he finds his best bream-bed deals in the corners of main-lake pockets. He’ll make long casts to cover water, especially in areas where he’s seen bluegill on the bank, and retrieve the bait slowly with steady rod pumps.

“Usually, this time of year, if you get them to follow, they’re going to eat it,” Cherry said. “But if I see one follow it and he doesn’t commit, I’ll just kill the bait. Usually, if you kill it, they’ll nose down on it and sometimes you can make them bite.”

Skylar Hamilton

The clear water common to a highland reservoir like Table Rock, Beaver Lake or Cherokee can make fish spooky, but Hamilton uses the ultra-visibility to his advantage by targeting big roamers that follow deeper bait schools during the summer months. His weapon of choice: an oversized topwater walker like the Strike King Mega Dawg.

“Even in the middle of the day, you can call up a giant this way,” Hamilton said. “You might call that fish up from 30 feet. They crush it; it’s absolutely insane.

“I wouldn’t do this all day in a tournament unless it was really effective. But if I’m trying to catch one over 6 pounds, that’s what I’d do.”

Hamilton focuses his effort by scanning for bait schools in creek mouths and looking for big arches suspended within striking distance. Preferring the bone color, he insists a spacious saunter outshines a rapid cadence. (Think bass drum versus snare drum.)

“You want it to be as wide as possible, so I’ll take the split ring off my topwater and tie a loop knot directly to the bait,” he said. “I feel like I get more direct reaction to my rod that way.

“You want it to walk a foot and a half to 2 feet each way. That actually slows down your retrieve quite a bit, but the bigger fish want something easier to eat.”

Rigging tips: Hamilton fishes his big topwater on 30-pound braid to ensure good hook penetration, but he adds 6 inches of 20-pound monofilament leader to prevent his front hook from tangling in limp braid. Also, a feathered rear treble helps seal the deal because when it flares, it resembles the “paint brush” look of a shad tail. The more realistic profile tends to minimize the last-second turnoffs.

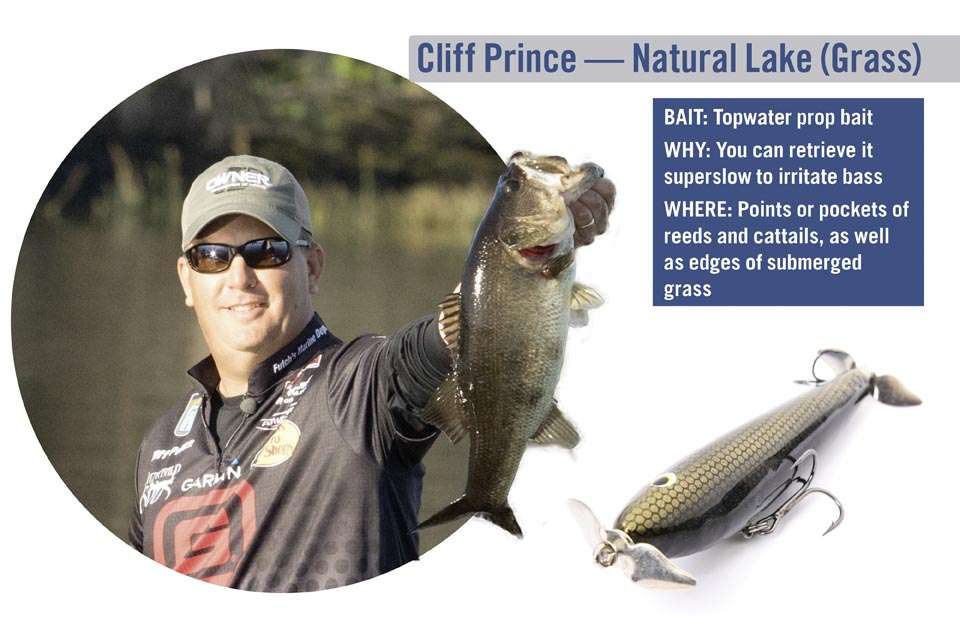

Cliff Prince

Give Prince props for knowing how to tempt big ’uns — no, literally give him props. The Florida stick knows that a lot of true studs will pile into the vegetation as the postspawn transitions into summer. For these scenarios, Prince finds a Greenfish Tackle TAT double-prop bait does a good job of hovering in the sweet spots and creating momentary bursts of utterly obnoxious intrusion.

“I would be looking for submerged hydrilla or open holes in the grass,” Prince said. “With reeds and cattails, I’d be looking for a pocket inside, or a point on the outside.

“I don’t have to walk a prop bait; I can throw it and let it sit there and let the rings settle. You just leave it there and it irritates them so bad they crush it.”

Of course, using those props is part of the performance, and Prince gets his best response with a downward rod motion, similar to how he’d work a popper. He fishes his bait on a 6-foot, 8-inch medium-heavy Fitzgerald rod and either 15- to 20-pound monofilament for open water grass or 30- to 40-pound braid for the dense, vertical cover.

“You have to let the fish tell you what they want,” Prince said. “Sometimes, they want it sitting dead still after you’ve twitched it three times. You just have to [vary] your cadence to figure out what they want that day. They may want you steady working it or you may have to throw it out there and twitch it one time.”

Originally appeared in the Bassmaster Magazine 2019.