It was the best of times. It was the worst of times. For bass anglers, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was busy like beavers building dams across the South, creating huge, man-made reservoirs where black bass would soon thrive.

For others, it was a time of constant struggle. “Segregation Now. Segregation Tomorrow. Segregation Forever.” As a newly arrived outsider, the words of Alabama’s Governor George Wallace echoed in my mind. Here I was searching for Mt. Meigs Road, an avenue running east-west into downtown Montgomery and off Dexter Avenue, where Dr. Martin Luther King had preached his message leading to his historic “I Have A Dream” speech.

It was a time of dreamers. A former Montgomery insurance salesman, Ray W. Scott Jr., was among them. He dreamed of bass fishing as a business. Of making his passion for bass fishing as a tournament competition rival baseball as the favorite American pastime. Ray’s newly spawned Bass Anglers Sportsman Society (B.A.S.S.) was achieving a toehold and the support of some 2,000 members.

My dream was also about to become real, but as the new editor of Ray’s Bassmaster Magazine. I’d arrived with heart-stopping emotion. If you imagine a bad sign or omen forecasts the future, understand this: The office for Ray Scott’s upstart headquarters for B.A.S.S. was housed directly across the street from the Montgomery Monument Company. The company’s display of granite headstones lined the curb.

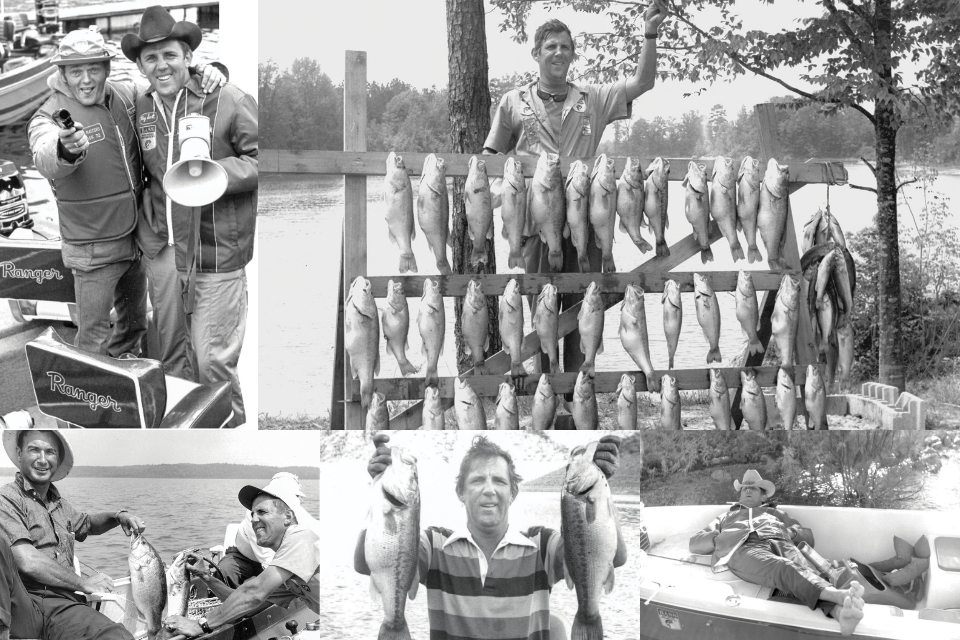

Before Ray Scott held his first tournament, he was a passionate bass angler. He, like other fishermen, judged the success of a day on the water by how many bass would be hanging off a bragging board at the end of the day. However, once he realized how precious these fish were to his fledgling company and to sporting anglers across the nation, he created catch and release and would work tirelessly (although the occasional nap was needed) to shout this ethic through his bullhorn to all who were willing to listen. Photos: B.A.S.S. archives

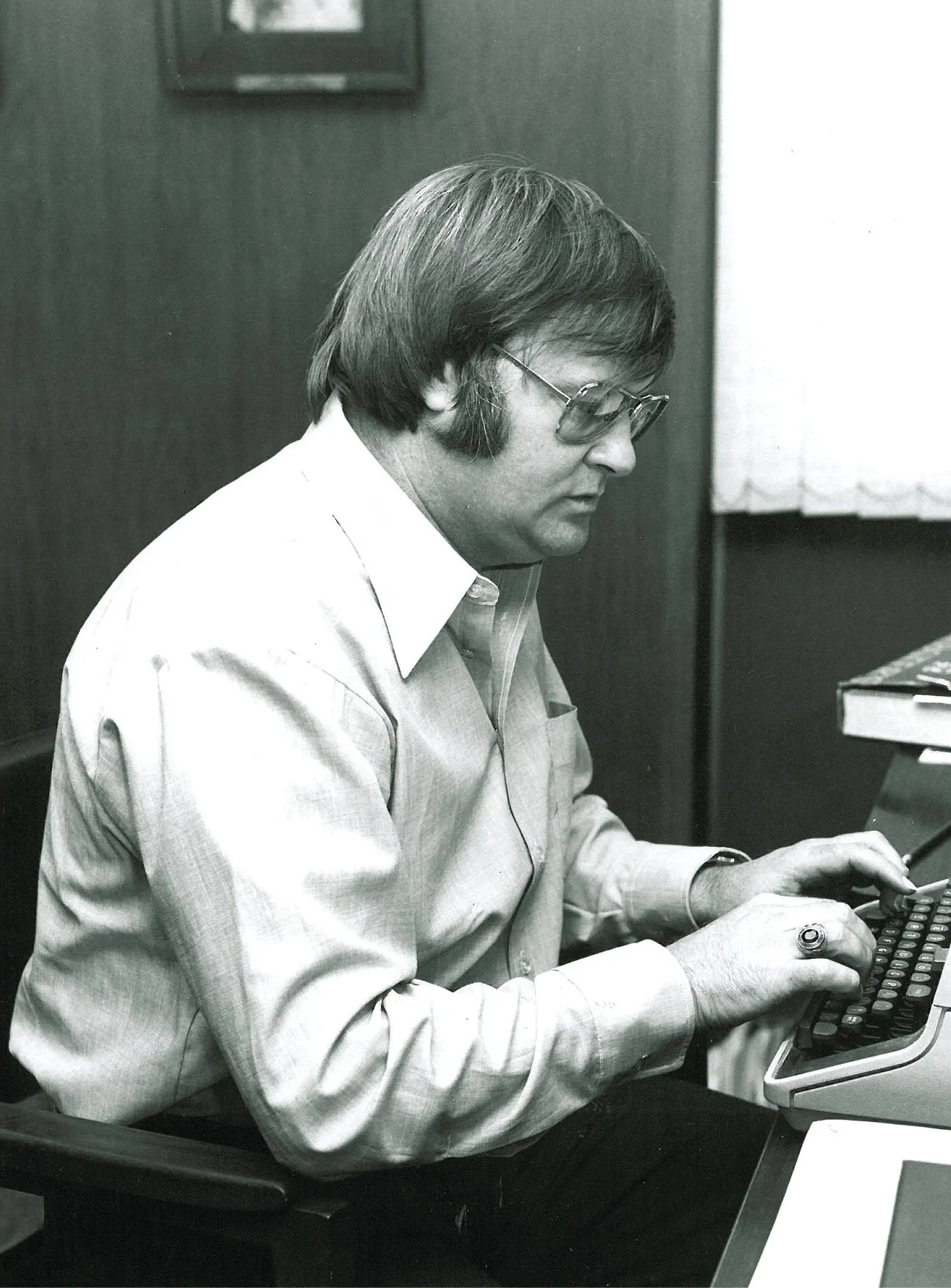

The front door to B.A.S.S. was the back-alley entrance to the Woolard Building, a construction firm and architect business. The architect had moved out, and the new editor of Bassmaster was moving in. The office wall was lined with a waist-high shelf and indirect fluorescent lighting where blueprints were once scattered about. The lone piece of furniture was an adjustable Pro-Throne.

The pedestal seat once housed in a bass boat could be adjusted nicely to fit the working space for a typewriter, a used, portable Royal typewriter that Ray had purchased from the Montgomery Pawn & Loan for $55. Beside it was a cardboard box.

“That’s the file for Bassmaster,” he told me. “Maybe there’s something in there to get started with.” And, Mr. B.A.S.S. marched down the short hallway to his desk to answer a phone call.

The cardboard box was from a local pickle canning company. Was this more likely Pandora’s box, another foretelling curse? “Caught in a pickle” is the Southern expression to signify a difficult situation, I understood.

From Ray, I would learn the company’s slogan was, “Whitfield Pickles. The pickle with the perfect pucker. Picked at the peak of perfection by particular pickle-picking people.”

As the B.A.S.S. tournament weighmaster, Ray would challenge the fishermen to repeat after him the slogan for a $1 bet. He seldom lost his dollar to the tongue-tied anglers gullible enough to try.

From the handwritten stories by B.A.S.S. members buried in the pickle box emerged the Winter 1970 issue of Bassmaster Magazine and the upfront column, “Scott On The Line,” which introduced members to me as editor of Bassmaster. “I think they’re going to call me the publisher. Cobb will be in the front of the boat and I’ll be fishing in the back.”

The column continued explaining how we met at the announcement of Ray’s first All-American Invitational Bass Tournament in 1967 in Springdale, Ark. At the time, I was the outdoor editor of the Tulsa Tribune in Oklahoma. It was the beginning of an association with Mr. B.A.S.S. and the sport of bass fishing that continued for over 50 years and many milestones in the amazing history of living inside Ray’s dream.

The pulse-pounding chords of “I Was Born To Be A Dreamer” represent the life and times of Ray set to music. His was an All-American success story. Many doubted his vision to place the black bass on the throne, toppling the lordly trout as ruler of sportfishing. There were no professional bass anglers. There were negative voices in the press and concerned fishing tackle manufacturers who viewed the noble sport of fishing as “contemplative,” NOT a competition.

The subtitle to Ray’s success and climb up the business ladder might well be “Prospecting and Selling an Idea to Fill a Need.” Think P.T. Barnum meets Sam Walton in the parking lot at Walmart, with a tent meeting held by a Billy Graham-like crowd mover. Face it, people. It takes a special salesman, a unique individual, to be able to assemble 20,000 cheering fans inside a public auditorium to witness grown, hairy-legged men (Ray’s words) weigh in bags of fish.

But it happens, as it did, in a crowded arena in 1984 in Pine Bluff, Ark. Rick Clunn was waiting on the results of his catch to be called by Ray. The scales were flanked by two future presidents of the United States, Vice President George H. W. Bush and Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton. With both hands raised, Ray calmed the standing-room-only crowd. The drama built. This was showmanship. This was salesmanship. This was “Made In America.” Ray’s voice boomed over the crowd’s cheering, “He’s done it folks! Rick Clunn has won the BASS Masters Classic World Championship!”

As Ray Scott legitimized and popularized bass fishing tournaments, B.A.S.S. started to grow. Bob Cobb and Helen Sevier (right middle) came on board early to help make Ray’s dream become a reality. Popular outdoor personality Grits Gresham (bottom) started writing for Bassmaster Magazine, which was the first vertical publication for bass fishing. It wasn’t long before B.A.S.S. needed a bigger office and an official logo. Bass anglers now had a society in which to belong, a shield that would protect their passion, and it was headquartered in Montgomery, Ala. This growth also created celebrity anglers like Tom Mann … and even celebrity bass, like Mann’s Leroy Brown (left). Photos: B.A.S.S. archives

Clunn’s victory remarks were spellbinding. “Only in America can you dream like this, to think of chasing little green fish and make $40,000 in three days.”

Competitive bass fishing had arrived. Ray’s wild dream had turned the fishing world on end. The 1984 Classic storyline was so compelling, Ray wanted the universe to come on board. The B.A.S.S. news department cobbled together the available TV news tapes and produced a 30-minute program titled The Winning Tradition, shown on The Nashville Network (TNN). The Bassmaster Tournament Trail would come riding into cable sets and living rooms across the country each Sunday as the long-running The Bassmasters TV series played on TNN with an average audience of 1.4 million bass fishing fans.

The backbone of B.A.S.S. was its 650,000 members and bass clubs organized as state federations.

Think of the multiplier required to go from the 106 entries in the 1967 All-American Tournament at Beaver Lake to a global membership that size. Every one of them was dedicated to chasing after “little green fish” (i.e., largemouth, smallmouth and spotted bass species).

The lure to catch the holy grail of bass fishing, the 22-pound, 4-ounce world-record largemouth, caught by George Perry in 1932 from a south Georgia oxbow lake, is the dream all dedicated Bassmasters share. Ray, among them, chased largemouth bass from A to Z — from Alabama to Zimbabwe. Seeing the future through the lens of remote Africa, he arranged in 1981 for 2,500 Florida bass fingerlings to be airlifted to Zimbabwe B.A.S.S. Federation members to nurture for future stockings.

Ray is on record saying, “If I wanted to break the record, it might shock you to learn my next cast would not be in California or Texas. I’d head to southeastern Africa.” Ray had learned that the offspring from the original Florida bass stockings were producing trophy-size catches. In 2004, a Zimbabwe B.A.S.S. member, Maxwell Mashandure, caught an 18 1/4-pounder that caught the bass fishing world’s attention. Once again, Ray’s uncanny way dictated the spread and growth of bass fishing’s future.

The crude, 6-foot craft powered by a kayak paddle used by Mashandure was a paradox to fishing boats used in today’s B.A.S.S. tournaments. From aluminum johnboats launched in the first tournament on Beaver Lake to $50,000 bass rigs, Ray’s Bassmaster Tournament Trail has generated an ever-growing bass fishing industry. As Earl Bentz, the acclaimed Triton boat builder, said: “Ray Scott built a one-of-a-kind sandbox, and we all came to play in it.”

To fill a need, they came. Johnny Morris, a Missouri-based tournament pro, witnessed the void in bass tackle and created the mega-chain of Bass Pro Shops. Forrest Wood, a White River fishing guide, converted his homemade johnboat into the No. 1 selling Ranger bass boat. Carl Lowrance’s sonar Lo-K-Tor guided bass pros to find deeper structure and schools of bass untouched by the bank beaters.

The “Don’t Kill Your Catch” movement stood at a pivotal point in the hot summer of 1972 in the office of the Mississippi Game and Fish Department. Cigar-smoking, foot-stomping Avery Wood, his face flushed with anger, refused to listen to Ray’s plea to allow the B.A.S.S. tournament to release bass alive.

Ray didn’t blink. He fired back at the unwilling Mississippi game commissioner, “If you think you’re going to stop us from catch and release, you’re going to have to show up with a baseball bat and whack every bass in the head.”

The commissioner’s cigar spewed ashes on Ray’s clenched jaw. “We don’t want you to turn those fish loose that have been stressed or diseased and go out and spread disease all over the lake,” demanded Wood, “and we’re not going to allow it.”

Ray’s tournament release concept had just gotten underway with the 1972 Bassmaster Tournament Trail, when the bass boys stopped at Ross Barnett Reservoir near Jackson, Miss., and ran head-on into the roadblock.

It didn’t take long for B.A.S.S. to jump from a couple thousand members to membership in the six digits. This became a powerful group when unified for the benefit of the environment and angling access. Ray used this powerful voice with governors, presidents … and even a first lady or two. Ray was integral in the passing of the Clean Water Act, as well as Wallop-Breaux legislation that continues to fund fishery management. Photos: B.A.S.S. archives

The future of bass fishing, in Ray’s mind, stood at the crossroads. He believed, “We’ve made some progress. Fishermen’s attitudes are changing.” But, not in Mississippi.

A local group, the Mississippi Association of Bass Clubs, showed no concern for “live release” of tournament-caught bass. The basic facts were the MABC didn’t want to arouse any adverse publicity as to their tournament weigh-ins. They even contacted Governor William Allen’s office and turned it into a political pawn.

In his heart, Ray felt there was no scientific evidence to support the protest. “We were trying to do the right thing for the future of bass fishing.” Nothing fazed Avery Wood’s mindset or deflected orders from the governor’s office.

However, a determined Ray was prepared to start the Rebel Invitational the next morning. Over a bullhorn he bid the anglers good luck, urged them to keep their catch alive and prayed for a safe return for the fishermen and fish.

Ray Scott had drawn his catch-and-release line on the shoreline of Ross Barnett Reservoir and fully intended to stand behind and defend it. But, Mississippi game rangers waving baseball bats didn’t show up. Somehow. Some way. There was a game changer: They showed up with an aerated tank truck to assist with the weigh-in and live release.

But there was a catch-22 tied to it. The Mississippi fishery biologists were eager to determine the survival rate of tournament-caught bass. They would study the delayed mortality with the fish held in a netted-off area a mile from the weigh-in. This was mid-August. The holding area selected averaged less than 2 feet deep. The combination of shallow water, no shade and 90-degree water took its toll. Only 25% of the bass were able to swim away when the nets were removed.

Despite the horrid conditions and results, Ray could celebrate a moral victory. From that lowly one-quarter survival rate, the average success rate of his B.A.S.S. weigh-ins would reach 98%.

The nearsighted critics jested about him as “Crazy Scott.” His followers carved Ray in the mold of industry movers and shakers like the iconic Walt Disney giving us laughter and the “Mouse House,” as if Mickey Mouse meets Billy Bass. Or like the maverick Ted Turner, producing CNN’s 24-hour cable news. Pioneers with an idea and the self-purpose to follow through to the end. Ray, in my opinion, most imitated Ted Turner’s style of “Do something: Lead, follow or get the hell out of the way.”

At one juncture in his life, Ray thought long about the Christian ministry and becoming a preacher. Essentially, he did; he became a “fisher of fishermen,” gathering his flocks by teaching bass fishing and preaching anti-pollution messages. In 1970-71, Ray and B.A.S.S. conducted one-night seminars from coast to coast, rallying bass anglers to save our fishing waters and “peg a polluter,” to end industrial use of public waters for profits and dumping waste.

In building B.A.S.S., Ray had, at the heart of the organization, the future pulse of the bass fishery. To keep it beating, he worked to organize bass anglers into a political force: To sue polluters, improve fisheries management and research, share bass fishing how-to methods, create bass angling heroes as role models for future anglers and strengthen the future by changing bass tournaments to catch and release bass alive after weigh-in.

But that’s not the full story of Ray’s lasting legacy to bass fishing.

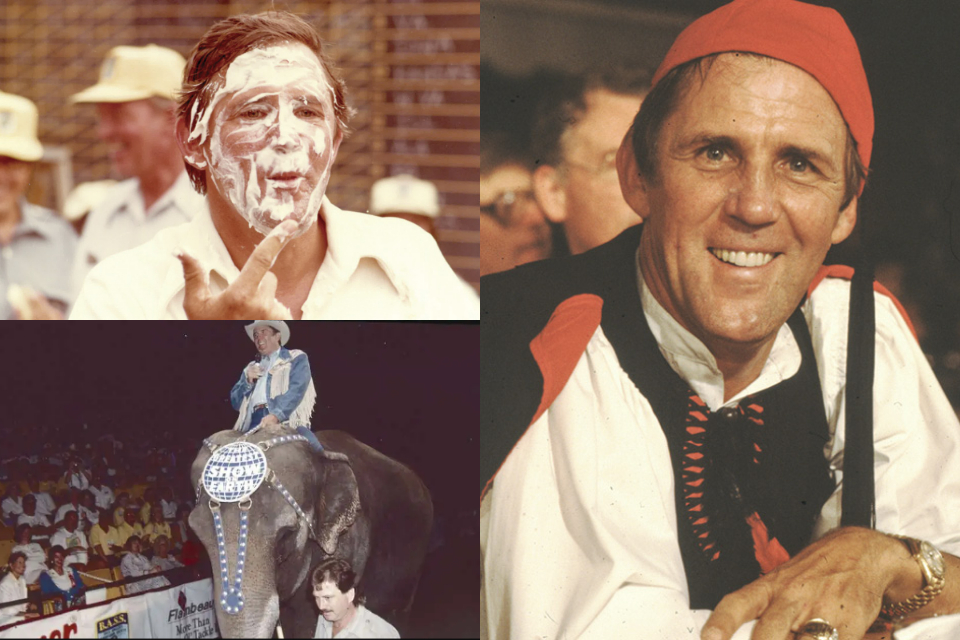

Above all, Ray was an entertainer. Whether participating in a pie-throwing contest at an early Bassmaster event or dressing up for theme night at the Bassmaster Classic, he would have the crowd eating from the palm of his hand. Photos: B.A.S.S. archives

Today, more and more bass anglers are wholeheartedly dedicated to his catch-and-release policy. Ray has been praised for his contributions to conservation and the growth of the bass fishing industry, and he was proclaimed by Field & Stream Magazine as one of the most influential sportsmen of the 20th century.

Ray’s undeniable impact on the future of the black bass is forever sealed in his founding of B.A.S.S. and seeing its future in “Don’t Kill Your Catch.” He believed, “If we don’t take care to release the bass, there will be fewer and fewer bass to catch, and some will stop fishing.”

Historians say that the best among us are remembered for 100 years or so. The rest are soon forgotten. The memories of past heroes and champions, like yesterday’s headlines, soon fade away. The apostle Paul said that he “served God’s purpose in his own generation” and departed.

Bassmasters are entrusted with the legacy Ray Scott is leaving behind: To believe in the will to achieve the impossible, to dream the improbable, to defy the doubters and critics, to claim victory against great odds, to believe in an idea and to have faith in the gospel to carry it forward. Ray always said God guided his path and had His hand in everything B.A.S.S. achieved.

“The righteous person faces many troubles. But the Lord comes to the rescue each time.” — Psalm 34:19

Originally appeared in Bassmaster Magazine 2022.