Even in the age of bass fishing specialists, versatility is still ballyhooed as a winning ingredient. It's the angling equivalent of a balanced offense, bobbing and weaving, hitting to all fields. And if you believe what you read, it's the textbook way to never have a bad day.

So, if versatility is so revered, why is Woo Daves known as a "junk fisherman"?

Is it because his front deck is littered with rods? Or that his array of winning lures reads like a laundry list from Bass Pro Shops?

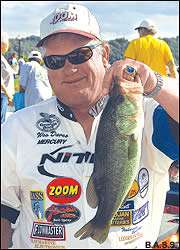

In winning the 2002 New York CITGO BASSMASTER Northern Open presented by Busch Beer, Daves once again brought respect to a moniker that he himself embraces. Call it junk fishing or being versatile, Daves doesn't care. It is a freewheeling style that has served him well for many years and made him a force to be reckoned with at age 57.

And it served him again on the Hudson River in early October, producing the top string of 32 pounds, 5 ounces for three days of fishing.

"This feels wonderful. All I was looking for this week was to make a check. Sometimes people give up on you, so this win is pretty special," remarked Daves, making reference to his self-imposed hiatus from tournament fishing.

Although some could make the argument that the confused, transitional conditions found on the Hudson played right into his hands, Daves did what every other angler could not. Making the victory even more remarkable, he approached the tournament more as support staff to help his son, Chris, vie for a CITGO BASS Masters Classic berth than be a final round scene-stealer.

< Heading south from the launch at Catskill Point, Daves wanted to put as much distance as possible between himself and his son's water. The unseasonably warm weather had stalled the seasonal migration into the creeks, scattering bass and making them difficult to pinpoint.

Making matters worse, the summer haunts of the Hudson bass — large, floating mats of water chestnuts — had withered and been torn apart by forceful tidal surges. Without these recognizable points of reference, most anglers were forced to hunt-and-peck their way to limits, a game in which Daves is the undisputed master.

Daves approached Wappinger Creek, guarded by a low-slung railroad bridge, on the first day with little to go on. His practice had not revealed much, other than the fact that he would have to find an area that offered a multitude of targets.

On all counts, Wappinger Creek delivered. With an assortment of structure and cover elements ranging from water chestnuts to laydowns to grass, Daves put a tacklebox of options to work. Zoom French fry and U-Tail worms, Stinger jigs and Zoom craws all had their moments as Daves struggled to piece together a four fish creel for 7-13 and 30th place. It wasn't much, but it was a start.

Meanwhile, a little farther north, Rhode Island's Mike Wolfenden was setting the water on fire. With a first round limit of 16-3, it seemed as if he was fishing on a different planet from a field that produced only 10 other creels busting double digits.

Although Wolfenden was outwardly reserved, on the inside, he must have been doing back-flips. Unlike most others, he had figured it out.

Recognizing that fish milling around creek mouths needed somewhere to hold until they

decided to move in, he began looking for a likely area. What he discovered was a quartet of sunken barges lying on a gently sloping bank in 5 to 18 feet of water. With two of the barges intact and the other two broken in pieces, this main river structure — positioned next to a decaying chestnut patch — offered a host of target options. And Wolfenden made sure his Bandit crankbait and Yamamoto Senko hit every one of them.

As a storm front brought cooler temperatures and rain for the second round, Daves returned to Wappinger Creek with only one goal in mind: make the Top 50 cut. Convinced that a surviving patch of water chestnuts held quality fish, Daves focused on a 50-yard stretch. In two passes through the zone, he boated a trio of 3-pounders that would eventually anchor a solid 14-4 limit, boosting his total to 22-1, and grabbing sole possession of fifth place.

Even so, the 2000 BASS Masters Classic champion was still looking uphill at Wolfenden, who seemed to be building a nearly unstoppable juggernaut.

With a respectable 11-5 limit, he was nearly 5 1/2 pounds ahead of Daves, who was barely on the radar screen of being in contention. The bite seemed to be getting tougher for everyone, so the prospect of final day heroics appeared remote.

As quickly as the storm front arrived, it moved past, leaving behind a cloud-studded blue sky. However, the return to balmy weather was no advantage for Daves, especially with a progressively later high tide being held back by a persistent south wind.

With an empty livewell at 10 o'clock, Woo found himself in a real pickle. The bulging higher tide had trapped him in the creek. Unable to slip beneath the bridge, he had no choice but to salvage something from Wappinger Creek.

Running out of options and time, he focused on the only targets he had not yet fished — the old concrete foundations positioned just in front of the bridge itself. With casts that paralleled the slightly submerged cement slabs in 8 feet of water, Daves turned up three quality fish in a 40-minute span, slow rolling a 3/4-ounce Ledgebuster spinnerbait. Later, a fourth bass was added to his catch.

Determined to free himself from the jail that Wappinger Creek had become, Daves exercised his only option. In a move made famous by Randy Blaukat, the veteran pro removed his engine cowling, pulled his drain plug, and with a half-sunken boat, scraped beneath the railroad trestles.

Racing upriver, Daves began hitting every bridge support he could find. Eventually, he found himself directly across the river from the Catskill weigh-in site, where he hooked and landed his fifth fish, a 1 3/4-pound smallmouth that snapped the line as it entered the net. The junkman had made his rounds.

At the same time, Wolfenden had been stymied not by his water, but a bad dose of angling luck. After giving his amateur partner free rein to cast anywhere he wasn't, Wolfenden's sportsmanship turned into a hot hand for John Imbesi of Cairo, N.Y. Cranking the barges toe-to-toe with Wolfenden, Imbesi held on to his second round lead, added four fish for 7-5, and took home the amateur title with a 21-4 total. On the other hand, Wolfenden settled for just two bass and second place in the pro division, with 31-15.

In 16th place after Day 1, Lee Bailey Jr. of Amston, Conn., buckled down during the second round for a 14-11 limit that eventually led to a third place finish with 29-8. By targeting rock points up and down the river with a Senko rigged wacky style, Bailey found a pattern so strong that he stayed on shore during the final practice round. What he could not overcome were wind and tide conditions that made it very difficult to correctly present his lightly weighted plastics.

A fourth place tie at 29-1 between Florida veteran Steve Daniel and local ace Tom LaVictoire of West Rutland, Vt., graphically illustrated a tale of two patterns.

Although Daniel initially believed his jerkbait approach for smallmouth wouldn't produce a winning weight, two lost fish during the final round were all that separated him from the top spot.

As for LaVictoire, his intimate knowledge of the Hudson tides was at the core of a shallow jig bite that centered on main river riprap and bridge pilings. The turning point in his fortunes came during the second round, when heavy overcast weather pulled the fish away from his target zones.

Classic invitations handed out

For the first time in tournament history, five anglers had their CITGO BASS Masters Classic fortunes decided before New Year's Day. Since the Northern Open on the Hudson River was the third and final event of the newly redesigned Open series, a nail biting tournament-within-a-tournament developed among those in contention.

Holding on to his first place points lead, Indiana's Koby Krieger emerged as the overall leader for the Northern Open division, with 567 points. He will be joined at the 2003 Classic in New Orleans by Lee Bailey Jr. of Connecticut, 559 points; Michael Iaconelli, New Jersey, 556; Randall Romig, Pennsylvania, 555; and David LeFebre, Pennsylvania, 552.