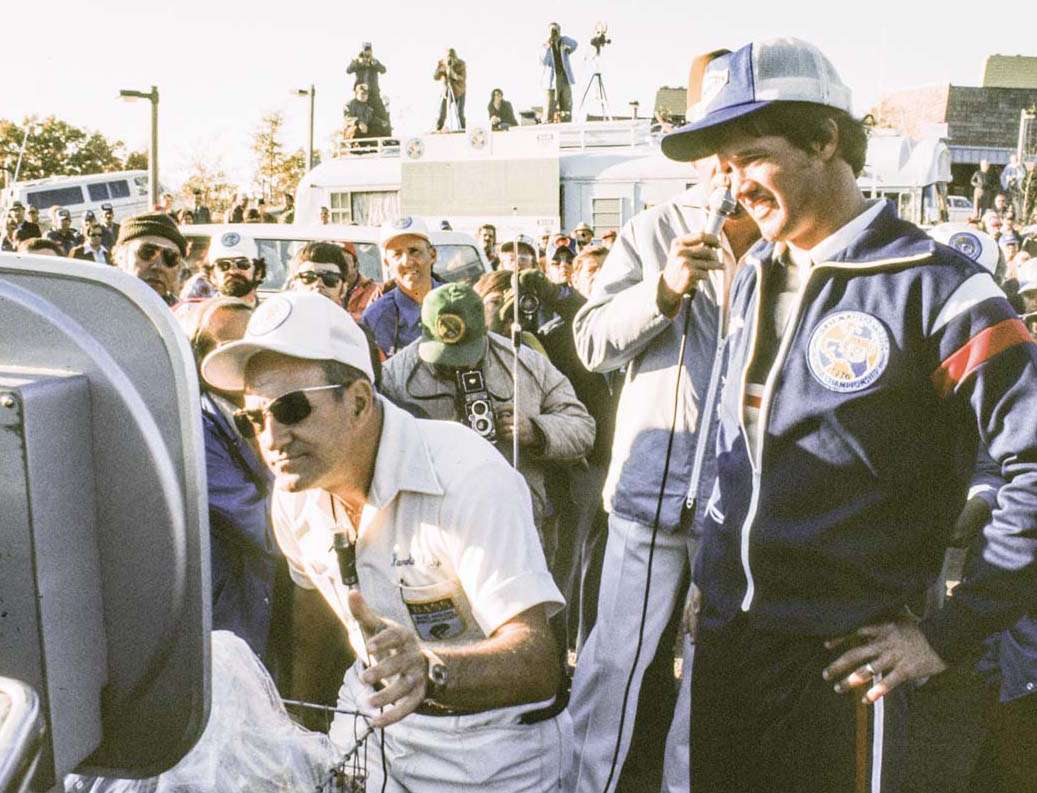

For those who were there, and perhaps for some who read about it afterward, the 1990 Bassmaster Classic on the James River is still remembered as Rick Clunn’s fourth Classic victory, with a lure he designed specifically for both the tournament and the river. Nearly 10 pounds behind leader Tommy Biffle at the beginning of the final morning of competition, Clunn boated more than 18 pounds that day and won by more than 7 pounds.

The untold story of that Classic occurred on the second day, when Clunn’s press partner was a Chicago-based writer who barely said a word to him the entire time they were on the water. Instead, he simply took notes.

On the drive back to Richmond, the writer did start talking. He was actually a statistician who covered the Chicago Cubs, and he had recorded every one of the 2,343 casts Clunn had made that day. Of those casts, Clunn had 25 strikes and caught 24 fish.

“I had never heard numbers like that before,” remembers Clunn, “and initially, it sounded like I’d had an incredible day of fishing, catching 24 bass. Then it hit me. I was making nearly 100 casts per bite, and that’s a pretty poor percentage. I was throwing to cypress trees on virtually every cast, so I was not making purely random casts. I knew fish were using those trees.

“I kept thinking about this, about how to improve my percentage of nonrandom versus random casts, and the next day I probably had the finest fishing day I’ve ever had on the water, execution-wise. I’ve had a lot of days where I had maybe two hours during a day that were perfect, but never a full day like the final day of that Classic.

“In my fishing today, more than 25 years later, those numbers the writer told me about are still on my mind. I wonder how many casts we make to places where there aren’t even any fish, and I have worked even harder, trying to improve those percentages in my fishing.”

Clunn’s memory bank is filled with lessons like these, not at all surprising from the fisherman many consider to be the greatest bass angler of all time. Clunn fished his first B.A.S.S. event, the Texas Invitational on Sam Rayburn, in March 1974, and today at age 72, he is the oldest Bassmaster Elite Series competitor. Now, he has competed in more than 400 bass tournaments from Texas to Florida, New York to California. The boyish, almost innocent features so noticeable in his mid- to late 20s have been replaced by a short, trying-to-turn-gray beard and occasional glasses, but overall, he’s still slim, sharp and, at times, surprised at the influence he has had on the sport.

Words and statistics do not adequately describe his career; more than any other angler, Clunn has symbolized and defined the sport of competitive bass fishing around the world for more than four decades, and no one can guess how many youngsters he has influenced to start bass fishing or become tournament anglers.

Because statistics are important, however, here are a few: In B.A.S.S. competition, he has 15 victories, including four Bassmaster Classic wins. He also has two second-place finishes, one third and three fourths — a total of 15 Top-10 finishes in 32 Classic appearances. In 1988, he won the Bassmaster Angler of the Year title. While competing on the FLW circuit, he won three FLW Tour events, finished in the Top 10 a total of 20 times and competed in six Forrest Wood Cups. He was the first angler to win the U. S. Open twice, and before there was an FLW, he won the 1983 Red Man All-American.

He has always been a student of bass fishing. It began with his earliest experiences walking behind his father, Holmes Clunn, as they waded and fished Oklahoma streams, and continues to this day. Looking back, he attributes much of his success to that intense passion for the sport and his ongoing desire for knowledge.

“My first thoughts of becoming a bass pro came during my time with the Pasadena [Texas] Bass Club,” he says. “But I probably really started thinking seriously about it right after Bobby Murray won the first Bassmaster Classic, in 1971. I read about it in Bassmaster Magazine, and when he was handed that check for $10,000, it struck me as a pretty fun way to make a living.

“I was working for Exxon then, in a job where I was just making ends meet from month to month. Most people around me were doing the same. What I really wanted to do was something that I loved to do, so I resigned to become a fisherman. When I started, I was only fishing 15 to 20 events a year, which left more than 30 weeks when I didn’t have anything to do.

“That’s when I started guiding on Lake Conroe. It brought in money but it also started me on an incredible learning curve for techniques and allowed me to stay in shape physically and mentally for the tournaments. I kept guiding for just under 15 years.”

Clunn needed his guiding business, because his tournament winnings during his first season totaled just $1,200. In that first B.A.S.S. event in 1974 on Sam Rayburn, he finished 24th and won $275. More than the fishing, he remembers being intimidated by some of the other already well-known pros who were also competing, especially Bill Dance, Roland Martin and Ricky Green, who won the event.

Still, Clunn used the event as a learning experience, watching and studying the anglers around him. Green was the first fisherman Clunn had ever seen who fished standing rather than sitting, so he started doing it himself. Jimmy Houston made easy underhand-style casts, so Clunn learned how to do them, as well.

He qualified for both the 1974 and ’75 Classics but did not do well in either one, and by 1976, he was, in his own words, “pretty much at the end of the rope.” If he didn’t do well in the 1976 Classic, he didn’t know if he could continue in the sport. He started studying past Classics, almost from a scientific angle, to see what he could learn, to determine what he was missing.

“That study was like an epiphany,” says Clunn. “What I found was that all the Classics to that point had been held in October, all were on man-made lakes, except for Currituck Sound in 1975. Even more importantly, all had been won in the same places with the same lure — in tributary creeks with spinnerbaits.

“So, even though the 1976 Classic was still on a ‘mystery lake,’ I decided that regardless of where it was held, I was going to go fish a creek with a spinnerbait. That’s what I did, and I won.”

There’s a little more to it than that, of course. The 1976 Classic was held on Lake Guntersville, and early on the second morning, Clunn caught four bass weighing nearly 25 pounds with his spinnerbait in less than 10 minutes. All competitors’ boats had CB radios then, and press observers reported their pro’s catches each hour for all to hear. When Clunn’s 25-pound catch was announced, the stunned silence on the CBs was clearly noticeable. Fellow competitor Bo Dowden said later he almost threw his rod into the lake in disbelief and frustration. Clunn went on to win with 59 pounds, 15 ounces, the heaviest winning weight for a Classic up to that time. That is when the Clunn legend began.

“That win gave me tremendous confidence because to me, it showed that the concept of seasonal bass movement patterns really was valid,” emphasizes Clunn, “and I feel like it gave me a big advantage. I fished every tournament the rest of the year just like it was the Bassmaster Classic, adding to my own understanding of bass patterns. The following April, I won the B.A.S.S. Champs tournament on Percy Priest Reservoir, and that October I won the Classic a second time down on Lake Toho in Florida.”

The Clunn legend could have easily become derailed at Toho, especially since on the first morning he got lost in the fog and couldn’t find the lock leading down to Lake Kissimmee, where he had planned to fish. He got mad and just decided to fish the next weedline he came to.

“I picked up a buzzbait, and on about my third or fourth cast I caught a 7-pounder,” remembers Clunn. “I still had my confidence, but at Toho, I didn’t have the knowledge to back up that confidence. Everything I’d been doing that related to seasonal patterns went out the window, but that 7-pounder gave me a place to fish, and that’s where I spent the rest of the tournament. On the last day, I only had two strikes and I caught both fish. One was too small to keep, but the other was larger, and that’s the fish that won for me. To be absolutely honest, I got lucky in that tournament, but winning still gave me even more confidence.”

Clunn’s runner-up finish in the 1978 Classic at Ross Barnett is largely overlooked in light of Bobby Murray’s victory there, but late the final afternoon, Clunn hooked the bass that would have won that Classic for him.

“Yes, I do still think about the ‘what-ifs,’ if I had landed that fish,” he admits. “To me, there is no doubt it would have won the tournament, because I didn’t bring in a full limit that last day. The way I lost the fish is what hurts, because normally, I don’t lose more than a handful of fish the entire year, and I had this fish hooked well.

“The bass hit in lily pads and immediately wrapped two or three times around a stem, so I had to go into the pads to get it. I got to the fish and was just ready to kneel down to grab it when it came off. Execution is the difference between winning and losing in many events. I had generated the bites to win but I failed to execute.”

At a tournament at Lake Gaston, Clunn had another dramatic experience that has also shaped his fishing ever since, the day he was paired with Fred Young, the maker of the legendary Big O crankbait. He knew of Young and the Big O but did not have access to any of them, so Young gave him two to use.

“I wasn’t having a very good tournament, and that afternoon, out of courtesy to him, I tied on one of his crankbaits and started casting it,” Clunn recalls. “Fred was sitting down in the back, and after watching me a few minutes, he said, ‘Son, let me show you how to fish that lure.’

“He made a cast,” Clunn continues, “then started turning the reel handle faster than anyone I’d ever seen before. He made two or three casts, then gave it back to me. ‘You never stop it,’ he said, ‘unless you hit something. When you do hit something, pause it, then you burn it again. Some will hit it slow, but if you burn it, they’ll try to swallow it.’

“At first, I wasn’t sure whether to believe him, but everything he said was absolutely true. Later, I won the Missouri Invitational on Lake Truman, an FLW event on Beaver Lake, and came close many other times, doing exactly what he taught me. I had started my crankbait fishing in the bass club with a Hellbender and felt pretty confident with it, but Fred Young opened a whole new world for me that day, and I still follow his advice.”

Clunn used crankbaits to win one of the most memorable tournaments in his career, the 1984 Bassmaster Classic on the Arkansas River, where he brought in 75 pounds, 9 ounces, and won by more than 25 pounds. His father was gravely ill during that time, and Clunn thought very seriously about withdrawing in order to be by his father’s side. Fortunately for everyone involved, and especially for the sport itself, he stayed to compete and gave everyone a tournament no one can forget.

Not too surprisingly, another of his most memorable wins, to himself as well as to his legions of fans, came in the 2016 Bassmaster Elite Series tournament on the St. Johns River. In that event, he caught a 4-pound bass near the end of the second day that pushed him inside the cut-off for the third day, when he brought in a monstrous 31-7 haul that jumped him into the lead. A California angler who became a tournament pro because of Clunn’s influence, Skeet Reese, helped him carry his fish to the weigh-in stand. Clunn finished with a four-day total of 81-15; at the time, he was just four months short of his 70th birthday.

“That’s one reason I love fishing so much,” he explained afterward. “I don’t have to be able to run a 100-yard dash in under 10 seconds, and I don’t have to be able to jump high enough to dunk a basketball. In fishing, all you have to have is passion. I have always believed you can fish at a high level even when you’re older, and the St. Johns win validated that, and that 31-7 was the third-best catch I’ve ever weighed in.”

On a slightly different note, Clunn admits the field cuts have affected his career as much as anything over the years. The first cut after two days eliminates any possibility of recovering after one bad or even mediocre day. Had he not caught that single 4-pounder near the end of the second day on the St. Johns, Clunn never would have had the chance to catch the huge stringer the next day and go on to win.

That brings Clunn back to his never-ending quest to improve his percentage of nonrandom casts. The way you beat others, he says, is by converting as many random casts into nonrandom casts as possible, which he was able to do at the St. Johns.

“Most anglers don’t ever think about this,” he says, “but to do it, your awareness on the water has to be fine-tuned. You have to develop the discipline to remove the random casts and learn to focus more closely on where bass are most likely to be. I’ve made my career by fishing fast, simply making more casts during the day than my competitors. Kevin VanDam has fished the same way, and also with a lot of success.

“But today’s electronic technology is changing all this and making fishermen more efficient. Sonar units now show a picture that completely surrounds the boat and pinpoints not just potential cover bass could be using, but sometimes the fish themselves. Younger anglers are embracing this new technology faster than us older ones who learned the basics on simple flashers. They may make only 500 casts all day, but 400 of those casts are to specific targets or even to fish, so they’re not random casts at all.”

This has forced Clunn over the past several years to gradually give up the original Rick Clunn. He knows his old system of making more casts than anyone else doesn’t work anymore. This transition has not been easy, and it has created tremendous inconsistencies in his fishing results.

“I’m re-learning things,” he says, “even to the point of using lures I’ve never seriously considered using before. I don’t go out in practice and try to get 20 bites anymore. Today there are tournaments on some lakes where you need to think about a 4-pound average, and to catch that quality of fish, I’ve had to learn to slow down. I’ve learned to use certain big bass lures like swimbaits, and I’m having some success with that.

“I’m also learning about today’s depthfinders and electronics, too, but that will be a slower process.”

There are some who have planned their place in history, but Clunn has never been one of them. Now in his 44th year of competition, he is still fueled by his passion for the sport and his desire to learn more about the fish he’s trying to catch, and that part won’t ever change.