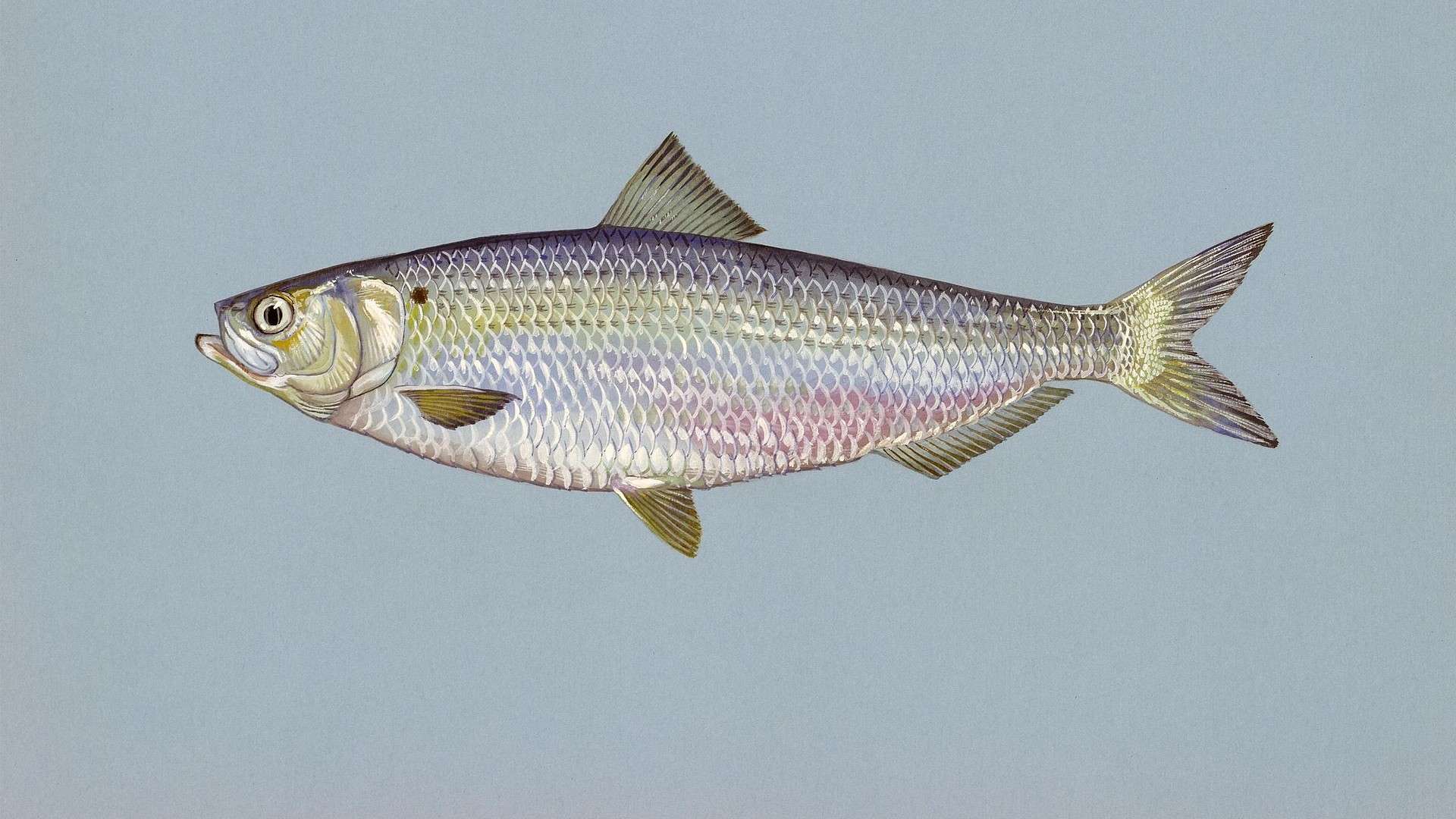

GREENVILLE, S.C. – Four-time Bassmaster Classic champion Rick Clunn famously advised that anglers who want to “understand the owl” need to “study the mouse.” The 55 competitors fishing this week’s Academy Sports + Outdoors Bassmaster Classic presented by Huk are dealing with what may be the tour’s most overwhelming variety of mouse infestation. The blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis) is an anadromous fish that may not be native to Lake Hartwell, but influences just about every move made by the fishery’s largemouth and spotted bass.

The contenders have different memories and understandings of how the spotted bass impact a tournament venue. Some, like 27 year-old Palmetto State angler Patrick Walters, cannot remember a time when there weren’t any bluebacks here. Others, like Alabamians and tournament long-haulers Gerald Swindle and Steve Kennedy, have watched the herring proliferate throughout the southeast, changing the personalities of particular lakes. A third class of anglers – including Idaho’s Brandon Palaniuk and Japan’s Daisuke Aoki, have had to make their peace with the outsized influence these fast-moving baitfish have on their predators at the inception of their careers. Aoki said the closest thing that they have in Japanese waters are wakasagi, but even they don’t behave the same way.

“I was lost the first time I fished on a lake with bluebacks,” former AOY Palaniuk stated. “It was my first year on tour in 2011, we went to Lake Murray while they were spawning. I liked it because you could fish really fast.” He subsequently realized that at other times of year the bluebacks, and the bass that chase them, are not quite so predictable. He offered up a Zen koan worthy of Clunn as a means of explaining them: “The best way to figure them out is to stop trying to figure them out. You can never have them dialed in. They’re too nomadic.”

Canadian Jeff Gustafson likewise expressed that understanding these prolific baitfish is simply a matter of recognizing the intellectual limits of that pursuit: “The more you know, the less you know,” he said. His home waters feature similar pelagic baitfish, like ciscoes and smelt, but it’s taken him several years of fishing southeastern U.S. waters to grow comfortable around the herring. They would seem to fit squarely with the electronics expert’s wheelhouse, though, and he intends “to keep the boat off the bank as much as possible.”

With warming air and water temperatures, most anglers fully expect a substantial migration of fish – especially largemouths – to the banks to engage in the reproduction ritual. Once they approach or fixate on spawning, eating may be the furthest thing from their minds, but that doesn’t mean that the bluebacks aren’t still living rent-free in their psyches.

“The fish just act differently,” Kennedy said. “You can throw a big glidebait around them when they’re up shallow and they won’t look at it. If it was a gizzard shad lake, they’d look. But I’ve yet to see a gizzard shad here. I’ve seen bluegills, threadfin shad, crappie and catfish. I’ll still have a glidebait tied on, but I’m not sure if I should.”

Despite his resistance to what the bass and the bluebacks are telling him, Kennedy has substantial familiarity with the substantial impact the bluebacks have on a fishery. He experienced the impacts of their illegal introduction on his home waters of Alabama’s Lake Martin, and saw how the lake changed.

“At first it fattened them up, but now it’s going in the opposite direction,” he said. “In the winter, I used to be able to go and jig up about 80 to 100 white bass, but they’re basically gone. Now you go up there and jig up about 80 to 100 bass, but they’re all little spots. Your best five out of those 80 might weigh 8 pounds.”

Lake Hartwell, however, is on the upswing. Bassmaster commentator and former Elite Series competitor Davy Hite has fished here longer than anglers like Walters have been alive, and while there were some growing pains related to the meal plan change, on the whole the fishery is better than it was in decades past. “The fish are healthier and better-looking than they were before,” he explained. “Honestly, as more and more generations of bass have lived with blueback herring, it has just changed their behavior. The biggest thing is that the fish just set up deeper. The threadfins just don’t stay as deep, so the bass are often out over 30, 40 or 50 feet of water.”

Kennedy said that one of his primary places bottoms out at 47 feet, but during Wednesday’s final practice session he “found bait lined up at 80 feet and that blew my mind.”

If this tournament were occurring a month ago, or in the heat of summer, or during the fall, there would be little or no question that unlocking the herring would be the primary means of figuring out and capturing the winning catch. With water temperatures nosing up to and hovering around the magical 60 degree mark, however, conventional wisdom says that a substantial portion of them should have spawning on their minds. That should be particularly true for the largemouths.

Not so fast, Swindle opined.

“Back in the day, the largemouth lived shallower and there were a lot more of them,” he said. “The challenge of fishing here in 1990 was probably a ‘five’ on a scale of one to ten, but now it’s a ten out of ten. The fish don’t move to the bank as fast. Some of them may be up shallow in the water column, but they’re doing it over a hundred feet of water. They don’t flood the shoreline. Instead, they creep up there.”

He’s one of the few anglers interviewed who thinks that the tournament can be won exclusively with spotted bass. “There have been several 17 to 18 pound bags of spots here lately,” he said. “A 3 ½ pound spot weighs exactly the same as a 3 ½ pound largemouth. I’m not sure why nobody understands that.” The notorious junk fishing expert may run and gun, but he’ll likely do a substantial portion of his damage with a spinning rod, focused deep.

While the tournament could be won in one or two drains that comprise pre-spawn highways, the flightiness of the schools of bait has the anglers ready to put ample hours on their outboards as well as their trolling motors. Walters said there’s a “95 percent chance” that the bait won’t be there or fired up when he arrives at his planned starting spot, so he has a rotation of 10 or 15 places to check in short order, with the expectation that “two or three will be good.”

Most of the anglers’ milk runs will involve at least an early morning detour deep before plying the shallows for a big bite or three. Palaniuk believes that the prevalent influence of the baitfish has changed where the bass spawn and the duration of the process. “The bluebacks keep them out much longer than they normally would,” he explained. “Before the herring were here they would probably live their lives and spawn entirely in certain areas, but now they don’t leave the bait as long. They might leave a ball of bait, go up for three days, and when the spawn is done they’ll go back and find the bait.”

He said that the water temperature on the main lake didn’t warm up as much between Sunday and Wednesday as he’d expected, but he still intends to take a two-pronged, shallow-and-deep approach.

“I’ll fish in 80 feet of water and I’ll fish in 8 inches,” he said. “The bigger bites are coming shallow, but the consistency is deep.”

Walters, the young gun who have never known a Lake Hartwell without blueback herring, and who won a Bassmaster Open here in September of 2020, thinks there’s something more to it than just deep and shallow, or deep vs. shallow, as the case may be.

“I’m taking a three-pronged approach,” he explained, summoning the same elusive Zen-like tone of his peers. “You can’t have a fork with just two prongs.”

Spots may be the main course, with largemouths as a much-needed lagniappe, but there may be no fish that plays a greater role in flavoring this weekend’s outcome than their fast-moving meals. Even anglers exclusively facing the bank can only ignore them at their peril.