Japan: Land of the rising sun.

The mantra seems fitting when you think of native child Takahiro Omori. Just two years ago, the Japanese angler won the CITGO Horizon award for being the most improved angler on the Tour. And this year, he won the CITGO Bassmaster Classic, proving he is the best in the world.

He's rising all right.

What is most impressive about Omori, who currently resides in Texas near famed Lake Fork, is not where he is in his professional angling career, but instead, where he came from.

The early years

Omori was born in Tokyo Sept. 4, 1970, and lived in the small village of Toyohashi throughout his childhood. His family was middle class, and his father took him fishing, starting at a very young age. "I can't even remember the first trip with my dad. I've fished ever since I can remember," reminisces Omori.

Trips with his father mainly included catches of carp and other indigenous fish. It wasn't until Takahiro (known as Tak by his peers) was 9 years old that he caught his first bass. He was with a small group of school friends. The boys dug up some nightcrawlers and swung one out from the bank with a single piece graphite rod, no reel. "We were so excited when I pulled that bass on the bank. Since bass are a foreign fish to Japan and were not very common when I was young, we had never seen one up close. So, it was a very special catch," smiles Omori.

It wasn't a month later when Tak found a discarded chartreuse plastic worm on the ground. "I put that artificial worm on my hook and flipped it out into the pond and nearly had the pole jerked out of my hand. The bass only weighed about a pound and a half, but it was the first fish I had ever caught on a lure. I'll never forget that fish," Takahiro grins.

After releasing that bass, Omori was hooked.

Honing his skills

Once in junior high school, he started studying Kendo. The martial art of stick fighting was not Tak's cup of tea. In fact, he hated the sport. It took him away from the water's edge.

"Although I studied it for nine years, Kendo was not a sport I enjoyed," Omori admits. "But, the training taught me very important lessons that I still use today in my fishing. When fighting, you have to be calm all the time, can't get too excited or too upset. You have to be calm to make good decisions — your mind, body and spirit have to be together. The same is true with fishing. You make good decisions, you succeed."

When not in school or sparring, Tak was casting for bass. In high school, he read about a bass fishing derby in Basser magazine (the first bass fishing publication in Japan) being held near Tokyo by an upstart organization called Japan Bass (JB). He and a couple of friends, all 15 years old, jumped on a train, rods and tackle in hand, and rode five hours to Lake Kawaguchi.

"I never caught a keeper," laughs Tak. "But we sure did have a great time!"

Participating in the event and watching all the anglers weigh in fish put the competitive drive in his blood. He could think of little else. "Basser magazine covered the 1985 Classic and I found out about BASS. I became a BASS member in 1986. My mom helped me get a money order to the post office to pay the dues.

"When I started receiving Bassmaster Magazine, I would pull out a dictionary and translate the articles. After I received my first issue, I knew that I wanted to be a professional fisherman. That was the first time I knew what I wanted to do for a living," remembers Omori.

Directly after graduating high school, Tak decided to move to Lake Kawaguchi to work on his angling skills. "Everyone thought I was crazy. My parents were pretty upset at my decision to pursue becoming a professional fisherman. Everyone tried to talk me out of it — my teachers, family and even some of my friends. Nobody understood my goal. In Japan, you couldn't really make a living bass fishing."

But Omori wasn't planning on staying in Japan.

For two years after moving to the lake, Tak worked three part-time jobs in order to save money to buy a boat, and more importantly, buy a ticket to the United States. In the meantime, he borrowed and rented boats to stay on the water as much as possible, practicing the techniques the BASS pros were using across the ocean.

While saving for his dream, Omori decided to fish a tournament against the rising stars of Japanese bass fishing in a JB qualification tournament. More than 200 anglers entered with hopes of earning enough points to qualify for the pro circuit.

He won.

"Winning that tournament gave me so much confidence. It really motivated me to achieve my goal. But at the same time, it was very frustrating. By winning I had become a pro angler in Japan, yet I still couldn't make a living," explains Tak.

Once the motivated young man turned 21, he had saved enough money for a round-trip ticket to Dallas, Texas. And more importantly, he felt he had the skill to fish against the best fishermen in the United States at the 1991 BASS Invitational on Sam Rayburn Reservior.

Tak lands in the USA

With an international driver's license and $2,000 in his pocket, Omori rented a car after landing at DFW airport and drove to Rayburn. "It was really confusing, because the steering wheel was on the wrong side of the car and everyone was driving on a different side of the road. It took some getting used to," Tak remembers. Luckily, he had time to practice.

Omori's plan was to fish the nonboater side of the BASS invitational on Rayburn, then drive to Alabama and fish an Invitational on Guntersville before heading back to the airport for his return flight. It was a 40 day adventure for the Japanese native, who still didn't speak a word of English.

"Luckily, I had met Gary Yamamoto at a tournament in Japan. He said that I could call him if I ever made it to the states. So, I did. He met me at registration and translated for me so I could properly enter the tournament on Rayburn," says Omori.

"It was so exciting being able to compete with the many fishing heroes I had been reading about. It was a great experience — except I didn't do so well." Takahiro finished 304th out of 310 anglers.

"There was over a month between the Rayburn tournament and the first day of the Guntersville event. Gary offered to let me stay at his ranch in Texas during the off time, but I decided to go ahead and drive to Guntersville to see what the lake looked like." Omori would sleep in his rental car most nights, only renting a hotel room when desperately tired.

On his way to Guntersville, Omori decided to swing by Bass Pro Shops in Springfield, Mo., and BASS corporate offices in Montgomery. "I was too intimidated to walk into BASS, because I didn't know English. So, after I drove around the parking lot, I headed to Guntersville," Takahiro admits.

Upon arriving at the north Alabama lake, Omori would practice from the bank. He also drove all the way around the lake to see what sort of cover and water quality different areas would offer. Did his homework payoff?

"I ended up in 256th place," laughs Takahiro. "But I met Rick Clunn and Larry Nixon. It was a very positive experience."

So, 3,500 miles on a rental car later and some valuable on-the-water lessons under his belt, Tak boarded the airplane headed back to Japan. "I realized how much I still had to learn. But, I had made up my mind to fish all six Invitationals the next year (1992)."

Becoming a BASS pro

Omori fished the '92 season without success. His first mark on the BASS trail came the following year. "I received my first ever check for an eighth place finish on Lake Eufaula. I caught an 8-12 and was awarded the big bass of the tournament. Funny thing is, after all these years on the Trail, I still haven't caught one bigger than that Eufaula bass," says Takahiro.

The turning point in Tak's career came in 1996 when he won his first BASS event on Lake of the Ozarks. (He was still commuting to Japan during the off-season.) Not only did the $35,000 purse help his situation, but the victory helped him secure some big name sponsors.

In 1997, Omori was granted an immigrant Visa and was able to live in the United States full time. "I decided to live near Lake Fork because it was the perfect spot to practice my skills while making some extra money guiding," explains Takahiro. He paid $2,200 for a travel trailer and rented a lot on the bank of the lake.

"I had a deal with a travel agency in Tokyo. They would send Japanese clients to me for guide trips. It's not a big surprise, but I think I'm the only guy around Lake Fork that speaks Japanese!" Tak laughs. "They even sent me a couple of newlyweds. It was pretty fun, and I sure needed the money to help me keep fishing."

He didn't have to rely on guide money for very long. In 2001, Omori had a coming out party. He won an FLW Tour event: $100,000. Then he won the BASS Open on Rayburn (his 10th year anniversary of his very first event on the same fishery): $50,000. He finished second in the BASS Tour event on Toledo Bend: $50,000. Then he made his first Classic, and he bought a nice three bedroom house (complete with swimming pool for testing lures).

A good year.

Omori was so excited about qualifying for his first Classic, he invited his parents, who were still not convinced professional angling was a real job. "My parents were able to stay four days. I was so excited for them to see what I had accomplished. And I felt like they were starting to understand my job," he says.

After the visit, Takahiro dropped his parents off at the airport. They returned to Japan. Three days later, Omori received the most devastating phone call of his life.

"My father had a massive heart attack and passed away. He was only 63. I felt so bad that I wasn't there. I canceled my first Tour event to return home for the funeral," Tak remembers.

Days after he arrived back in the states, terrorists attacked the United States. With the loss of his father and upset about the decimation and loss of life in the 9/11 attacks, Omori spiraled into depression. He had fallen from his highest high to his lowest low. He ended the year 138th in the points race on the Tour.

"Even though things were bad, deep down, I still loved fishing. As time passed, I regained my passion. Each day I would wake up feeling a little bit better," he explains. And by the end of 2003, everyone knew Tak was back as he was awarded the inaugural CITGO Horizon Award, given to the angler who made the best comeback from the previous year.

"The Horizon Award was a very important symbol to me. It made me realize I was ready to be competitive again," he says.

And back he was. In 2004, Omori made two cuts, cashed a check at every Tour event, ended ninth in the Angler-of-the-Year points race, and qualified for his third Classic.

Oh, yeah, and he won the world championship of bass fishing.

Returning home a champion

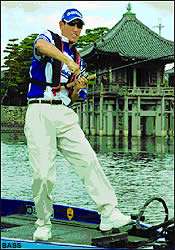

In celebration of his Classic victory, Takahiro flew to Japan for a victory tour.

Bassmaster and Japan's Lure magazine joined Omori for most of the trip.

The first stop was Popeye's tackle shop, located between the Osaka airport and Lake Biwa. When Omori arrived, the store was desolate. Ten minutes later, fans seemed to appear from nowhere, and lined up to get an autograph and picture. The bowing crowds were showing Takahiro the respect he had worked 18 years to receive. The respect he deserved.

Celebrations and press conferences would follow. The Japanese media were nearly brought to tears as ESPN highlights were replayed prior to a group interview. "We are so proud of Takahiro," says Yoshiyuki Tahara, editor of Lure magazine. "He has brought so much honor to our country with his Classic win. He is a hero for our country," Tahara believes.

Also traveling with Tak on his Japan tour was his mother. As the group bounced from city to city, Omori was always received with the utmost respect. Fans would stand outside the bus, bowing repeatedly as he passed by. And his mother finally began to understand.

"Respect and honor is everything in Japan. My mom now sees that a pro fisherman is respected, and I feel that she is finally proud of what I am doing. That is the best feeling ever," Tak admits.

The premonition

Perhaps the most fascinating chapter of Omori's story dates back to 1992. Upon deciding to fish all of the Invitationals that year, Basser magazine published an article on the young, hopeful angler. In the feature, Takahiro explained his 15 year plan. He had mapped out his career, and the Japanese magazine published his goals.

Unbelievably, the translated pages of the 12-year-old magazine state that Omori scheduled to accomplish the following professional milestones: In 2001, qualify for his first Classic — which he did! In 2004, win his first Classic — which he did! And 12 years ago, he planned that in 2005, he would win his first Angler-of-the-Year title.

Based on Tak's background — overcoming doubt, failure and depression to achieve his dreams — Angler of the Year may very well be the next achievement for Japan's rising son.