Born into current, riverine brown bass are aggressive strikers, powerful fighters and explosive acrobats. Every angler wants in on that action. But to be a successful river fisherman, you must learn to adapt. Free-flowing rivers are in a constant state of flux, which leads to shifting fish locations — along with necessary adjustments in fishing approach.

Granted, mid- to late-summer flows are generally less than the other three seasons, but even during this time of year, river levels can vary from extreme highs to extreme lows. A localized thundershower can increase the flow and color of the river in a matter of hours. Then, as quickly as it went up, the river will come down.

Or runoff from heavy rains in a distant part of the watershed may send the river to bank-full over a 24- to 48-hour period and remain that way for days.

At the other end of the spectrum, a prolonged summer dry spell will slowly decrease river flow; this scenario is becoming common as more areas are facing ongoing drought conditions.

Jeff Knapp, veteran smallmouth guide on the free-flow section of the Allegheny River in western Pennsylvania, must produce river bass for his clients under a wide range of conditions. “Some anglers complain they cannot catch smallmouth when the water is low and clear, while others lodge similar complaints about high and dingy conditions. So, they end up fishing only when the river is at a certain stage. However, low or high, smallmouth bass are catchable as long as the river is not at flood stage, which I define as over the banks and puking mud.

“I can’t say that I prefer a summer high flow or low flow condition more; each has its challenges and rewards,” Knapp says. “In general, I catch more smallies during low and clear conditions … but the average size of bass I catch during high and stained water conditions is better than the average size of bass in extremely low water.”

LOW FLOW

Low water during the summer allows bass to scatter into various niches, including shallow midriver areas — areas many anglers bypass. “This isn’t to say you won’t find fish near shore in low flows, but rather that bass don’t have to be there, as they do when the water is higher,” Knapp explains.

Dale Black, president of Gamma Fishing Lines, is a confirmed river rat who spends his angling time pursuing smallmouth bass. “While I catch bass during high flows, I prefer extremely low water because I can target feeding fish with pinpoint accuracy.”

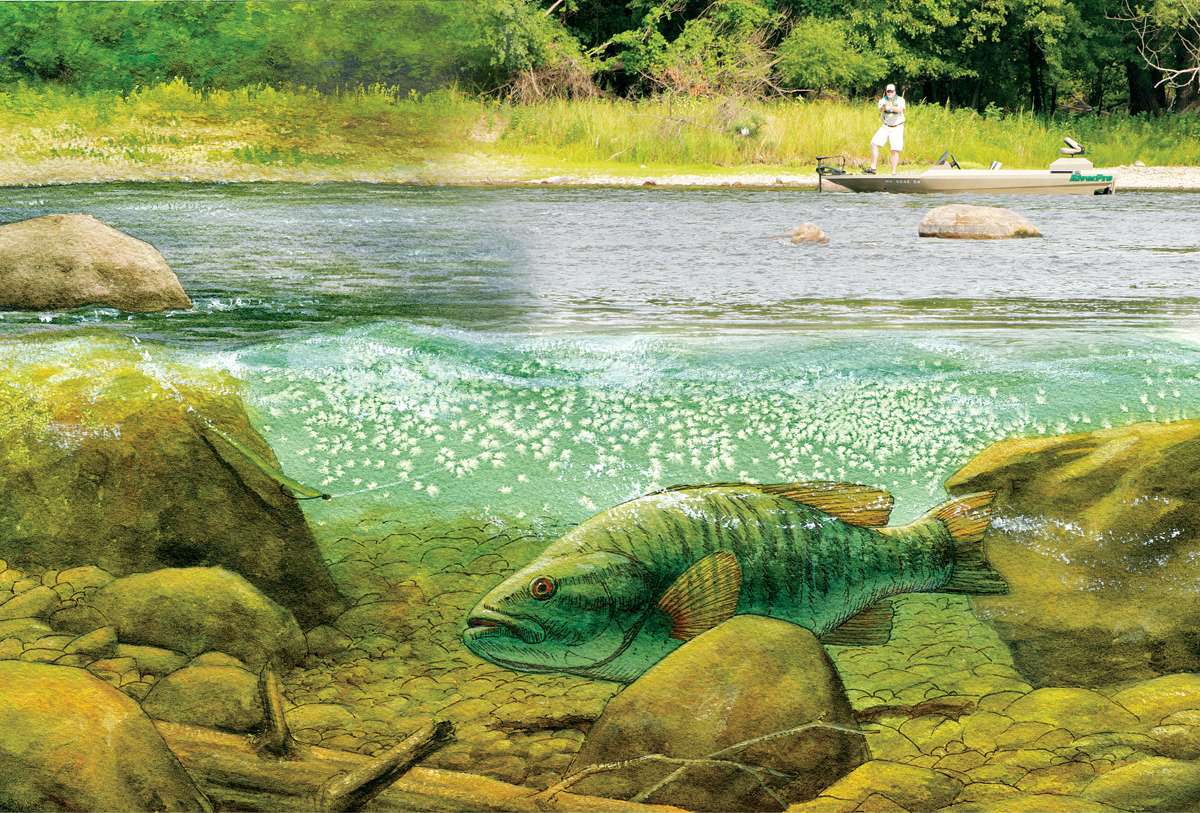

During the lowest flows, Black focuses his efforts on very shallow, fast-moving riffles and runs, targeting wash-out holes, which are small areas of slightly deeper water. “With water being low and clear, wash-out holes are relatively easy to spot as you drift by. Each site may hold several smallmouth even if you cannot see them against the rocky bottom due to their brown camouflage pattern.

“Usually anglers take a passing shot at such a spot as they drift by,” Black explains. “If you attempt to use the electric motor in this very shallow, very rocky and very fast water, the prop will not last very long. To effectively fish these spots, I’ll drop an anchor in a 4- to 5-mile-per-hour current in order to make accurate casts to wash-out holes, as well as the pocket eddy behind large midstream rocks.”

“Usually anglers take a passing shot at such a spot as they drift by,” Black explains. “If you attempt to use the electric motor in this very shallow, very rocky and very fast water, the prop will not last very long. To effectively fish these spots, I’ll drop an anchor in a 4- to 5-mile-per-hour current in order to make accurate casts to wash-out holes, as well as the pocket eddy behind large midstream rocks.”

“Scour hole” is the name Knapp applies to the smallest midstream pockets. “These places are very subtle, with depth measured in inches rather than feet. Yet they are deep enough to provide a comfortable holding site for a single bass to shoot out and grab prey as it passes by. Scour holes at the head of a riffle are particularly productive and are likely to hold larger than average size bass.”

Another of Knapp’s favorite summer low water areas is the run located below a fast-water riffle or rapid where forceful current begins to slow, also referred to as a riffle tailing. During low water, these sites are typically 3 to 5 feet deep. Unlike a scour hole, which holds a single fish, these larger areas are capable of hosting many bass if the bottom contains numerous basketball-size rocks to break the current.

When it comes to lure presentations for extreme low flows, these experts employ a limited number of baits.

“I’ve been told that I’m a one-trick pony for summer low water,” Black says. “I throw — or more appropriately, dead drift — a 4-inch stickworm probably 90 percent of the time. It’s going to be a Yum Dinger in green pumpkin rigged Tex-posed on a Mustad 4/0 Mega-Lite Hook with a 1/16-ounce bullet weight on 8-pound fluorocarbon. I’ll cast upstream of a shallow-water, fish-holding location and let the current carry it into the pocket. If it settles to the bottom before reaching the pocket, I’ll gently hop it along the bottom. This soft bait presentation is a representation of hellgrammites, crawfish, stone cats, darters, dace, log perch and a host of other bottom-hugging smallmouth prey found in riffles and runs during the summer.”

Knapp takes a different approach for a low-water presentation. His No. 1 pick is a suspending hard jerkbait presented with an erratic ripping retrieve. “My money bait for clients during low and clear water is the No. 8 Rapala X-Rap. In clear water, bass can be finicky, so it’s often necessary to go for a reaction bite rather than a feeding bite. That’s where the slash bait action of the X-Rap comes into play. Fishing it on braided line with a fluorocarbon leader lets me transfer a lot of action into the lure. That’s what is needed to trigger smallies: an aggressive, erratic retrieve with lots of head sway imparted to the lure but interspersed with pauses.

Knapp takes a different approach for a low-water presentation. His No. 1 pick is a suspending hard jerkbait presented with an erratic ripping retrieve. “My money bait for clients during low and clear water is the No. 8 Rapala X-Rap. In clear water, bass can be finicky, so it’s often necessary to go for a reaction bite rather than a feeding bite. That’s where the slash bait action of the X-Rap comes into play. Fishing it on braided line with a fluorocarbon leader lets me transfer a lot of action into the lure. That’s what is needed to trigger smallies: an aggressive, erratic retrieve with lots of head sway imparted to the lure but interspersed with pauses.

“It’s important to incorporate the pauses,” Knapp continues. “When ripping a suspending lure, a bass might be trying to eat it but misses it because of the lure’s sudden unexpected movements. Periodic stopping of the X-Rap gives bass a chance to zero in and grab the bait. The ripping gets their attention; the pause lets them nail it.”

The backup presentation for both anglers is similar: soft jerkbaits. “I make a Yum Houdini Shad dance, shimmy and shake like an injured baitfish,” Black says. “Rigged Tex-posed on a 4/0 Mega-Lite hook, this becomes my river search bait for shallow water. Sometimes bass eat it, but other times they just show their position with a half-hearted swipe, thereby allowing me to drift a Dinger to them. By fishing it on braid, I achieve solid hook sets even when drifting it in fast water.”

Knapp favors a Winco Custom 4.75-inch Solid Body River Darter. “I rely on this nose-hooked soft jerkbait to fish above shallow eelgrass beds bent over by the current, or in water that is too fast and too shallow to effectively work the hard jerkbait — places where an X-Rap would dig into the bottom. With the River Darter, I simply employ a twitch and drift presentation, thereby keeping the bait barely underwater.”

HIGH FLOW

When a river rises well above normal level, smallmouth will be forced to seek new feeding locations. During the initial rise, Knapp turns to gravel flats located along shorelines and on islands.

When a river rises well above normal level, smallmouth will be forced to seek new feeding locations. During the initial rise, Knapp turns to gravel flats located along shorelines and on islands.

“At low to normal flows, these flats are exposed,” Knapp says. “But when the water comes up a couple of feet, these flats become feeding zones for bass. A flat on an inside turn has a fairly light current and will draw baitfish. As the water reaches shoreline grass, this adds further cover options.”

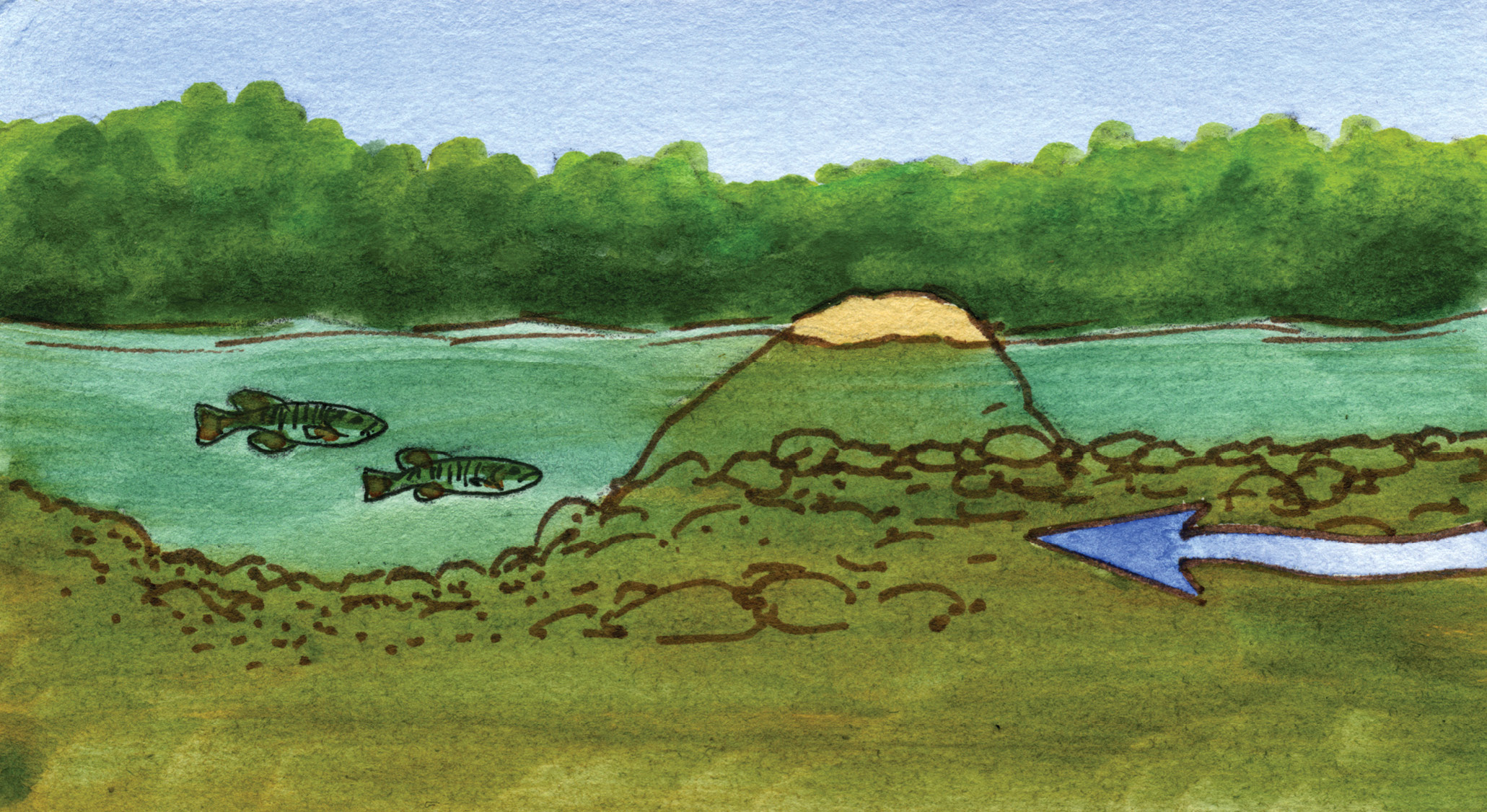

However, as water level continues to climb, Black is quick to point out that both baitfish and bass move tighter to the bank to escape forceful current. “I focus on shoreline pocket eddies formed by an irregular bank, gravel outwash bar or boulders. Also, I thoroughly fish the mouths of flooded tributary streams, which typically turn into an eddy as rising river water pushes against the inflowing creeks. However, it usually takes a day or possibly two of high water before bass and bait set up at these sites.”

Tributary creeks will begin receding while the main river remains high and murky. Now the stage is set for one of Knapp’s favorite situations. Bass that had moved into the flooded creek mouth now slide back into the river, positioning themselves in the plume of clearer tributary water along the downstream riverbank. The fish-holding potential of this kind of spot depends largely on the availability of shoreline cuts, embedded logs, submerged rocks or other cover on the downstream bank directly in the path of the clearer water.

Knapp and Black agree that high water during the summer increases the opportunity to catch bigger bass. Both anglers are in sync with their No. 1 weapon of choice: a spinnerbait.

Knapp’s tactic: Cast the spinnerbait next to a steeper section of bank and let it free-fall to the bottom. “My pick is a Terminator Short Arm Thump’r 5/8-ounce model, which is heavy enough to helicopter in the current. After it hits bottom, I’ll slow roll it a few feet. If I don’t get a hit, then I reel in quickly for the next cast. The money spot is close to the bank; that’s where you want your bait to spend the most time.”

Black’s tactic: Make a cast perpendicular to the bank and slow roll the spinnerbait as the boat drifts downstream, letting the current pull it along. “I favor a Strike King .38 Special Spinnerbait with both skirt and blades in either chartreuse or orange. It may seem a bit gaudy to some smallmouth purists who are stuck on muted, natural colors, but bold colors produce in dingy water. I particularly like to target flooded grass islands and boulder shorelines with a spinnerbait.”

If bass are unwilling to move on a spinnerbait, Black switches to a Booyah Baby Boo Jig with a Larew Biffle Bug Jr. The jig and bug combo is pitched to flooded shoreline cover, bounced once or twice when it hits bottom and then is swum slowly back to the boat.

With rising or slowly receding water, Knapp keeps a soft swimbait tied on one rod to fish the flatter shorelines, such as inside gravel flats. “It’s about employing a visible, realistic baitfish profile — big enough to be seen, but with subtle action. I fish it with a slow, steady swimming retrieve.” The nod usually goes to a Lake Fork Live Magic Shad rigged on a Gopher Tackle 3/16-ounce Mushroom Head Jig; the long-shank VMC Barbarian Hook in the mushroom head provides more consistent hookups.

While the river is still high and dingy colored but just starting to recede, Black switches to a 1/4-ounce shallow-lipped diver, such as an XCalibur Square Lip or similar square-lip diver. “With the water level starting to fall, bass begin pulling away from the bank. A diving crankbait is an effective way to cover ground while searching for smallies which are dropping away from the shoreline.”

WEEDS GONE WILD

With many smallmouth rivers across the U.S. experiencing exceptionally low flows for longer periods of time as the result of ongoing drought conditions, unusually thick aquatic vegetation growth is becoming a significant problem. In many northern flows, river eelgrass is expanding throughout shallow-moving water, taking hold in every nook that is not rock. While anglers are adept at working select baits over and through rooted vegetation, it’s the broken stem “floaters” that make lure presentation incredibly difficult, wrapping around both line and lure.

For example, sections of the Allegheny River were so choked with broken strands of eelgrass late last summer that every lure would become fouled as soon as a retrieve was started. Forced to employ presentations that did not require moving the bait, river anglers began target casting a weighted wacky worm on a weedless hook to openings in moving floating mats of grass and letting the worm drop vertically. Likewise, drop shot presentations were invaluable, with casts directed into wash-out holes and pocket eddies, utilizing enough weight on the rig so the sinker sat in place while allowing the slender drop shot bait to wave enticingly in the current. And instead of using popular hard-body topwater lures, some anglers switched to dragging a weed-resistant floating frog across the surface.

As the river rises and current starts ripping, baitfish will move to the banks and the bass will follow.

WHAT’S NORMAL?

Because river levels are constantly changing, “normal flow” is best described as a range of summer averages over a number of years. During normal summer flow on a typical free-flowing smallmouth river, bronze bass can be found in many different areas on a river. Generally, the most productive areas will be fairly strong current areas of firm bottom composed of sand, gravel, chunk rock and/or boulders. Smallmouth may search for prey on moderate-flow flats or take feeding positions in current breaks, where they can rest with minimum exertion while waiting for forage to swim or drift by. One particular type of fish-holding break is a current seam, created downstream of solid objects or when two somewhat opposing currents collide. Under extreme low flows, many current seams fizzle into nothing, forcing active feeding bass toward midstream structures. On the other hand, with a fast-rising river, current seams are blown out, pushing feeding bass toward the shore, sometimes into muck bottom sites rather than exclusively hard bottom sites.

To see the entire July/August 2013 issue of Bassmaster Magazine, click here.