I was a bass fisherman long before I was a lure designer. I built lures to fill a need or to do something that nothing else on the market could do. Back when I was in college at Louisiana Tech in Ruston, La. (I played on the football team with Terry Bradshaw, and when we weren’t playing or practicing, we were usually fishing), I built my very first lure — a lead jigging spoon that I poured in a wooden mold. It was crude, and you had to scruff it up a bit to make it shine like the commercial models, but it caught fish, and I was thrilled to have made something that worked.

After the spoon, I tried my hand at plastic worms, picking up the discarded plastics from friends and tournament competitors and melting them down to pour my own baits. It was cheaper than buying them in tackle stores, and I enjoyed it. I must’ve poured thousands of black worms with blue tails. That was my favorite color back then.

Before I ever got into designing and building crankbaits, I earned a reputation for tuning lures. When I was just getting started in the industry, the Norman Little Scooper was a hot crankbait, but only a few of them worked well right out of the box. Guys would give me their baits that didn’t run right, and I’d tune them and catch fish on them. Again, it was cheaper than buying them, and I was a starving college student with a fishing habit.

Back then — the early 1970s — there weren’t any real diving crankbaits to speak of. I still remember the first Bagley Balsa B I ever saw. It cost $6.50 (they still cost $6.50!), and I figured I could make one myself for less. Gas was 30-something cents a gallon back then, and $6.50 was a lot of money. Besides, I wanted a bait that would go deeper and let me fish the deep brushpiles in False River Lake outside Baton Rouge. I thought that if guys were catching bass out of that brush on plastic worms, I could catch them even better with a crankbait … if I could get it down there.

My first efforts had longer diving lips and a big balsa wood projection under the lip — I thought the lip would need that extra support. They weren’t pretty, but they caught fish. Soon I learned they didn’t need the extra lip support, and I started weighting my baits with bell sinkers, getting them down to 10 or even 12 feet on a cast.

Those kinds of depths were a big deal back then. We didn’t have the kind of gear you needed to get crankbaits to go deep — the longer rods, thinner lines and antibacklash reels that we all take for granted today. I was proud of those early deep-diving crankbaits, and I was absolutely killing the bass on them!

For about six months I was the guy to beat on our tournament circuit because there was nothing else on the market like my baits. Of course, there wasn’t much money to be won in local tournaments and I wanted to find a career in the fishing industry, so I started to sell my lures to the local tackle shops. It leveled the playing field in the tournaments, but it put a few dollars in my pocket and that was more important for a guy with a wife and family to support.

Selling those baits to the tackle shops also set in motion a chain of events that changed my life forever.

But that’s a story for next time.

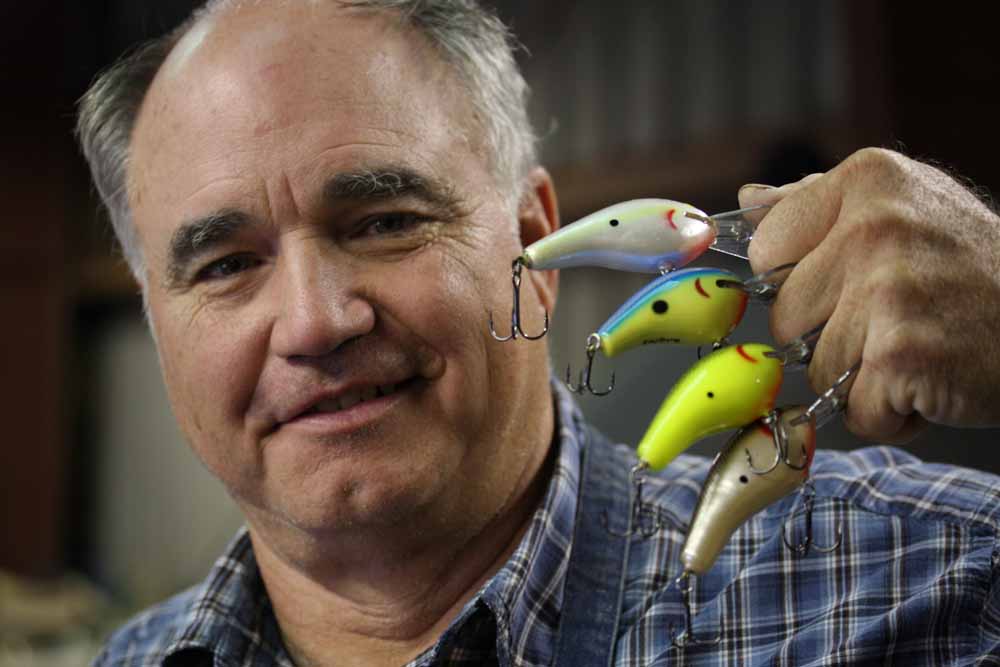

Editor’s Note: If you’ve paid any attention to the world of bass fishing over the past 40 years, you know the name Lee Sisson. He’s a legend in the field of lure design, having created the first true deep-diving crankbaits in the early 1970s and working for (alphabetically) Arbogast, Bagley, Bass Pro Shops, Cabela’s, Heddon, Mann’s, Strike King, Wal-Mart and others. If you haven’t caught at least a few bass on his designs, you probably haven’t done much fishing. And when one of his lure making competitors has an issue — this crankbait rolls over at higher speeds, that one won’t reach intended depths — it’s usually Sisson they call on to diagnose the problem. No one on the planet knows more about crankbaits and what makes them tick than “Dr. Crankenstein.”