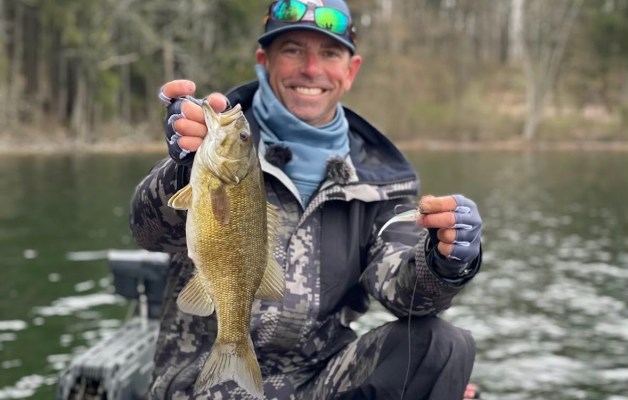

The Bassmasters TV co-host Mark Zona idled to a familiar dropoff on a southern Michigan lake, dropped the trolling motor and reached for his drop shot rig as he normally does when we share a boat.

I grabbed a jig rod — equally predictable for me on a hot, humid summer day — and pitched to the grassy edges.

Zona stared intently at his Humminbird screen while he jiggled his worm along the deep side of the break.

“We’ve got to find the bluegill,” he mutters. “If we do, and they’re on the bottom, good things will happen.”

He eased the boat away from the dropoff, and the depth plummeted to 25 feet. Blobs of bait appeared on the screen, and he began to smile.

“Time to toss the football,” he said. “Tie one of these on.”

What happened over the next two hours opened my eyes to an entirely new world of fishing on upper Midwest natural lakes.

“All I ever read in magazines growing up was ‘you have to follow the bait,’ but it was always in reference to shad — but we don’t have shad in many of our lakes,” he explains. “And after I started seeing bluegill tails sticking out of the gullets of big bass, I decided to start snooping around those big schools of panfish.”

The pattern idea was also fueled by his recollection of younger days spent fishing for bluegill with his dad during the hot summer months.

“After we’d catch a few bluegill, I’d pick up a bass rod and start casting around the area and catch bass,” Zona recalls. “Those experiences led me to believe that there was something going on out there that most anglers overlook.”

While the larger Great Lakes have a variety of forage, bluegill are the bass’ primary food source in most inland lakes.

Bass will follow them shallow in the spring and fall and deep during the summer and winter months.

“Most Northern anglers know the bass are hanging around the bluegill beds when they spawn early in the summer, but most forget about the panfish after the spawn,” Zona says. “But when the bluegill leave the shallows, schools of big bass follow them to deeper water.”

Zona says he’s had fabulous days fishing bluegill schools the moment the ice leaves Northern lakes in early spring.

“One day, I was graphing pods of fish suspended over 40 feet of water in an Indiana lake and started throwing a jerkbait,” he recalls. “I snagged numerous bluegill from 3 inches to 6 inches long.”

Zona switched to deeper jerkbaits and began fishing under the ’gills, where he found some of the biggest bass he’d ever seen in that lake.

“There was a two-week span when I caught 4 1/2- to 7-pound bass consistently,” he says. “These are fish we never see because we never have fished out there for them.”

Those schools of bluegill are easily located on electronics, appearing as a ball of baitfish hovering near the bottom in deeper water. The bluegill tend to school off deep flats adjacent to weedline dropoffs and almost always where some type of vegetation grows tight to the bottom.

To find them, simply idle around the deeper section of the lake until you start seeing balls of bluegill. Sometimes the schools will be broken into small groups, which means there is likely something on the bottom attracting them.

Also, you may notice larger, individual marks on the screen nearby — an indication that predator fish, like bass, are in that area.

Keep in mind that not all bluegill schools attract bass. The better fishing is found when those bluegill are holding close to deep grass.

Keep in mind that not all bluegill schools attract bass. The better fishing is found when those bluegill are holding close to deep grass.

On the other hand, if you don’t see the bass on the graph screen, it doesn’t mean they aren’t there. Sometimes gamefish are tucked tight to the bottom and aren’t easily recognized in deeper water unless you zoom in.

“The grass is the key, especially the ‘perch’ grass that is short and coarse,” Zona says. “I’ve found bluegill hovering over perch grass [in] anywhere from 17 to 40 feet of water — places that most people never consider fishing for bass.”

Bluegill will suspend, and the bass will linger beneath them. Those aren’t always easy to catch, except in the spring when the bluegill are sunning themselves in the upper 10 feet of the water column.

“In that situation, the bass are feeding up and dialed into the ’gills, so you can catch them on a jerkbait, or possibly a swimbait, that looks like a bluegill,” he explains.

During hot weather months, bluegill tend to suspend off the bottom during low-light hours, but will sag to the bottom once the sun is out. When the bluegill drop near the bottom, the feeding bell goes off for the bass.

“That’s why it’s wise to return to those areas where you found bluegill suspended early,” he says. “This bite tends to turn on later in the morning and can last throughout the day.”

The schools will move, too. Zona says he’s had terrific days on one spot, only to find the bluegill and bass have moved 50 yards down the grassline.

“But once you relocate them, you can light them up again,” he adds.

And that’s what he showed me that day. We fished 3/4-ounce bluegill colored football jigs tipped with Strike King Rage Craws in blue craw that were dragged or hopped along the bottom.

The results were phenomenal. Not only did we catch several bass and have doubles at times, but the fish were quality bass. Most ranged from 2 1/2 to 4 pounds — well above average for southern Michigan lakes.

Zona says this pattern will also work on Southern lakes that have large bluegill populations. Shad may be the primary forage, but a segment of the bass population feasts on bluegill, as well.

“I’ve heard stories of shellcracker [Southern bluegill] and bluegill fishermen hooking giant bass, so I know it happens,” he says. “The thing is, I haven’t spent enough time on those lakes to determine when and where it happens.”

Bait choices vary by season. Jerkbaits are best when the fish are suspended early in the year, whereas lipless crankbaits and swim jigs come into play when the bluegill move shallow.

“Everything I throw has bluegill colors — green pumpkin, a little purple and a hint of blue,” he says.

When they go deep, a 3/4-ounce Strike King football jig, a structure jig and a KVD 6XD crankbait are key players. You also can catch those fish on drop shot rigs in the sand grass, but the finesse baits don’t attract the same number of quality bites.

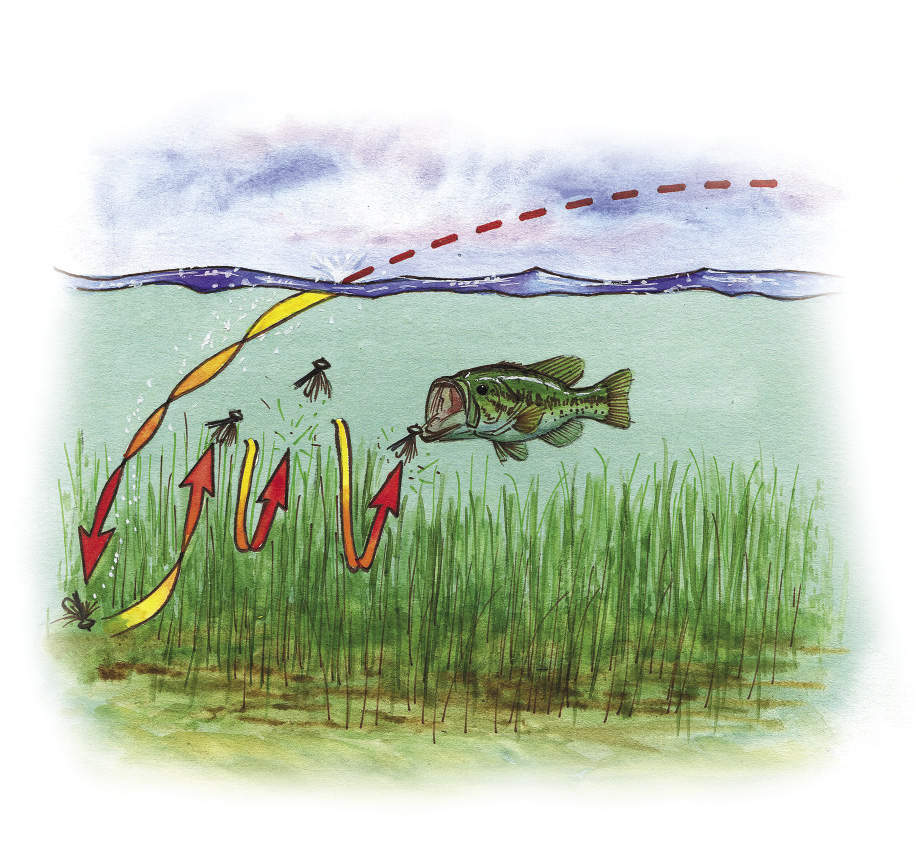

“I think the key is to replicate what a bluegill does in that deep grass,” Zona explains. “They’re rooting along through the short stuff for bugs and worms, so you want a jig or crankbait that moves accordingly.”

To do so, Zona casts his jig to the bottom and begins popping the rod tip similarly to the way shaky head worms are fished. The bait never stops, and when he feels it catch in the grass, he’s snapping the rod to make it pop free. That’s when the majority of strikes occur.

“Now, if I think the bass are suspended a little off the bottom, like earlier in the day, I may even swim it over the tops of the grass,” he says. “That’s also when a bluegill colored swimbait on a jighead can be deadly.”

Zona says it’s a natural reaction for anglers to look for the type of areas containing the most bass boats when looking for a place to fish or a dominant pattern.

“Not me, not anymore,” he says. “Now I look where all those tin boats with bluegill fishermen are anchored, and that’s where I want to fish.”

Originally published in 2014.