Mike Maceina has been a professional fisheries biologist for more than 30 years. He is a professor at Auburn University and a member of the Aquatic Plant Management Society.

Like most anglers, professional fishery and plant managers recognize that aquatic plants are important to maintaining quality bass fisheries.

Where they often differ are how and when aquatic plants should be “controlled.”

Spraying in the springtime, when bass are spawning and when herbicides can be most effective, is especially controversial. But does herbicide application hurt bass spawning? Other researchers and I at Auburn University decided to find out. The results may surprise you.

Aquatic plants provide valuable habitat that enhances largemouth bass reproduction, harbors numerous prey for bass to feed upon, and attracts both bass and bass anglers. But there can be too much of a good thing: Depending on the size and type of water body, 10 percent to 30 percent coverage of plants is ideal for healthy bass populations in most waters.

Water bodies can become choked with both native and exotic plants, such as hydrilla and Eurasian water milfoil, and when that happens, the forage base bass depend upon will change. Open water species such as shad will decline, and bass will have a harder time finding food. In some instances, the bass population becomes skinny and stunted from too many young bass in the system. Also, complaints and problems arise with some anglers who prefer less plant coverage, and with homeowners and other recreational water users who view excessive plants as a nuisance.

Control of underwater plants can be achieved using one of the following methods.

1. MECHANICAL HARVESTING

Some anglers think mechanical harvesting has minimal impacts, but many fish (including young bass) and aquatic invertebrates that support the food chain are killed with mechanical harvesting. In addition, when large areas are covered by plants, mechanical harvesting is not very effective, and it’s expensive.

2. BIOLOGICAL CONTROL

The primary biological plant control agent is grass carp, and I have studied its impacts for many years. In small ponds where no aquatic vegetation is desired, grass carp can be a great tool. However, in larger systems, I oppose mass stockings of grass carp where fish and wildlife are valued. Typically, stocking rates have been either too low to reduce the plants at all, or too high and most or all of the plants are eliminated. An intermediate level of plants cannot be consistently achieved with grass carp. Lake Conroe, Texas, is a prime example. Etched in the memory of many anglers, a high grass carp stocking in the early 1980s caused the complete and long-lasting removal of all aquatic plants (native and exotic). Since that time, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, along with local bass anglers, has been working hard to restore aquatic plants in this reservoir.

3. AQUATIC HERBICIDES

Herbicide applications are least popular among anglers, even though this method offers real advantages for fish and fishermen. First, any reduction in aquatic plants following a herbicide application is generally short term, especially when the chemicals are applied only to problem areas. In a few instances, whole-lake herbicide treatments have been conducted to remove or control exotic plants, some with negative results. Others proved to help the fisheries by permitting the establishment and proliferation of native aquatic plants.

TIMING

One of the more controversial aspects of herbicide use involves timing.

Herbicide applications can at times be more effective in spring — the same time bass begin to spawn. Largemouth prefer to bed on a sandy or hard bottom, with the male building a nest to guard and protect the eggs after spawning. The process begins when water temperatures reach about 60 degrees, and it takes about two weeks.

If aquatic vegetation is present, nests are often built close to these plants to provide cover for offspring.

This overlap in bass spawning and herbicide applications often results in conflict between bass anglers and aquatic plant managers.

To see if spraying herbicides in the spring has a negative impact on bass nesting behavior, the Fisheries Department at Auburn University in Alabama conducted a study using a common herbicide, Aquathol K, which was applied right on top of nesting bass in ponds. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has approved the spraying of Aquathol K at 0.5 to 5.0 parts per million (ppm), but lab tests have shown fish can live in 100 ppm of this chemical.

We used six 1/4-acre ponds, each stocked with a mix of 16 male and female bass that were 12 to 15 inches long. During this three-year study, the fish were stocked in late January each year.

Prior to introducing the bass, bluegill were stocked to provide forage. Nest building by male bass peaked toward the end of March, when water temperatures were 65 to 70 degrees, and we put a stick on the bank with flagging tape to mark each bass nest. Each pond had between one and six active nests.

We then sprayed Aquathol K at a rate of 5 ppm on top of the nests in three of the ponds. We also sprayed ordinary water on the nests in the other three ponds as a control to account for the act of spraying (not the chemical) and its effect on nesting behavior. From a distance, we observed the nest for the next few hours to see if the male fish would return. After this, we came back to the ponds nearly every day to see if the male was still active on the nest. Later in the summer, we collected the young bass produced during the spawn to see if there were any differences in production of young bass between treated and untreated ponds.

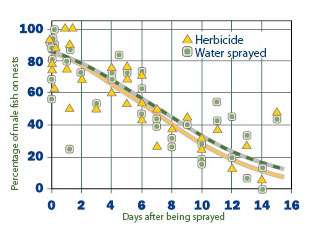

So what did we find? Right after nests were treated with either herbicide or water, all the bass immediately left the nest, but about 85 percent of the males came back to the nest within 15 to 30 minutes (see chart). About 50 percent of the nests were still active after one week, while only 20 percent were active after two weeks as most of the bass had finished spawning.

Sometimes a fish would leave but come back to the nest for reasons unrelated to either water or herbicide spraying. Ultimately, we did not see any differences in nest abandonment between those nests sprayed with water and those with the herbicide Aquathol K during the two-week spawning period. Furthermore, our sampling showed the production of young bass was the same in ponds sprayed with water as those sprayed with the herbicide. So, spraying these fish with Aquathol K did not hurt the spawn.

These results fit well with some of our previous work on Lake Seminole in Georgia where spraying herbicides in the fall prior to the bass spawn reduced hydrilla, which was then replaced by native plants, and opened up some sandy areas for bass to spawn. When the spawn started in early March, more adult bass used the coves that had a mixture of plants and sand than coves that were totally socked in with hydrilla.

Today’s aquatic plant manager recognizes the need for a good balance of plants in a lake or reservoirs. When controversy and conflict arise between bass anglers and plant control efforts, I always advise bass anglers to get involved early in the process. They need to attend public meetings and work with the management agencies to find solutions. Be proactive — not reactive. Bass anglers share the water with other anglers, homeowners and other recreational users. Trying to achieve or maintain a good level of aquatic plants for bass fishing, while keeping everyone happy, is a challenge, but it can be done.