They’re always watching, waiting, lurking inside the wire. Give them a window of opportunity and they’ll exploit it; often with devastating results.

The culprit: Neogobius melanostomus, the round goby — an invasive species native to the Caspian Sea. Entering the Great Lakes via bilge water from oceanic ships in the early 90s, gobies have since rapidly expanded throughout these waters.

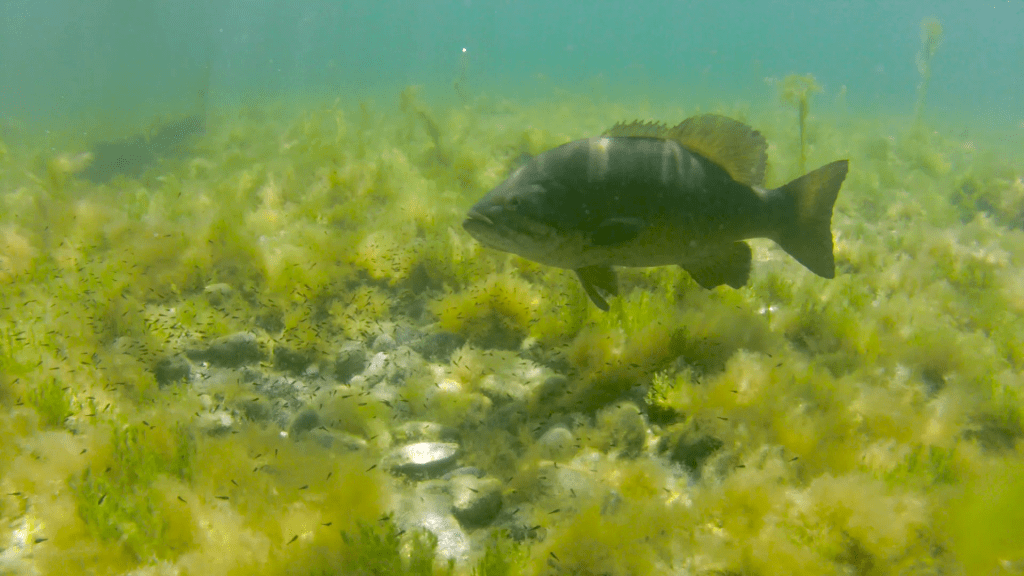

Among their targets: Smallmouth bass nests.

“Gobies are kind of a double-edged sword,” said Dr Bruce Tufts, Professor and Fisheries Biologist at Queens University, in Kingston, Ontario. “They’re a really easy food source for bass and they spawn several times a year.”

Christopher Legard, Lake Ontario Unit Leader for the New York Department of Environmental Conservation’s Bureau of Fisheries adds: “Round goby is an abundant prey item for bass, which has resulted in a dramatic increase in bass size and condition since goby entered the systems.”

No doubt, gobies have bolstered the fishery, as evidenced by the seven Century Club Belts earned during the past two Elite events at the St. Lawrence River — two in 2022, four in 2023. (The Bassmaster Century Club recognizes anglers who reach 100 pounds with four days of 5-bass limits.)

Show makers, for sure, but Tufts points out the goby’s larcenous nature.

“The bad part is that gobies are nest predators, so when spawning bass are removed from a nest for any length of time, gobies can get into the nest,” Tufts said. “They’ll either eat all the eggs or damage the nest to the point that the bass will abandon the nest (when returned).

“It’s a good and bad thing — everyone’s enjoying the good side, but we need to be aware of the downside.”

Exploiting vulnerability

Now, even the fiercest goby is no match for a nest-guarding smallmouth. However, while he’s not knocking tournament fishing, Tufts makes a sensible observation regarding the vulnerability of an unguarded nest.

“It’s not so much gobies on their own, but the combination of people (catching) fish at the time they’re on beds,” he said. “Gobies are able to get in there and basically eliminate the nest if they have enough time.”

In the big picture, one lost smallmouth bed may seem inconsequential, but multiplying the average number of eggs produced by a spawning smallmouth — Tufts said approximately 10,000-20,000 for large females — by the number of nests raided raises a valid recruitment concern.

For clarity, recruitment refers to the number of hatchlings that make it into that year class as adults. For example, if 2024 has a good recruitment, aging studies several years down the road would show strong representation from this year.

“Bass don’t need to have a giant year class every year, but they do need a decent recruitment every few years,” Tufts said. “If we get a good stable spring when the fish are spawning and the water warms in a uniform way, that helps (the bass) have a lot of eggs that survive and have a lot of young that survive.”

Conversely, Tufts said harsh spring cold snaps or stormy weather pushing cold water into spawning areas can doom bass nesting efforts.

Science says

Fortunately, the NY DEC’s annual smallmouth bass gill net surveys for eastern Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River have shown that gobies thus far have not inflicted a significant impact on smallmouth recruitment.

“The average number of smallmouth bass caught per gill net has been relatively stable in both eastern Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River since 2005,” Legard said. “DEC’s fisheries assessment programs indicate that smallmouth bass total abundance in eastern Lake Ontario and St. Lawrence River has been relatively stable since round goby colonization.”

Legard went on to state that the smallmouth bass assessments for eastern Lake Ontario have comprised at least 13 year-classes of fish each year since 2019. In the Thousand Island portion of the St. Lawrence River, the smallmouth bass assessment catch was made up of 14 year-classes in 2022.

“Multiple year-classes present in assessment catches indicates that there is some level of recruitment in the smallmouth bass population in both eastern Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River each year,” Legard said.

As Legard explained, assessment data presently presents no cause for alarm. Nevertheless, the goby’s taste for fish eggs keeps them on the watch list.

“Assessment data indicates that round goby do not appear to have a negative population-level impact on smallmouth bass in eastern Lake Ontario or the St. Lawrence River. However, round goby are nest predators, and have been observed preying on individual bass nests in both Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River.

“Nest predation by round goby does have a negative impact on individual bass nests. If nest predation is high in a given year, it can negatively impact smallmouth bass year-class strength and could have a negative impact on the smallmouth bass population in the future.”

Concerns and caution

Circling back to our opening topic, there’s no denying how gobies have boosted the “WOW!” factor for Bassmaster’s St. Lawrence River events. However, B.A.S.S. Conservation Director Gene Gilliland said it’s important to balance the awe with awareness.

“B.A.S.S.’ position is that gobies are an invasive species and, despite the fact that there have been these benefits to smallmouth bass fisheries in some places, the negative impact of gobies to other species and other fisheries (e.g. lake trout) has been well documented,” Gilliland said. “We don’t want people spreading them around; we don’t want them moved to other locations, because we don’t know what the unintended consequences might be.

“Like many invasive species, bad things can happen. We’d rather not take that chance, so we encourage anglers to avoid moving them.”

Bait bucket dumping — intentional or incidental — defines the unlawful transport of invasive species outlined in New York State Regulation 6 NYCRR Part 575. However, invasive plant and fish species are really good hitchhikers, so anglers can help prevent unintended invasive species expansion by thoroughly flushing bilges and cleaning boats, motors and trailers prior to entering another water body.

“I (often) hear anglers say, ‘Look how great the smallmouth fishing is on the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario, but there are fisheries for other species (like lake trout) that have gone downhill because of gobies and the people that fish for those species that aren’t smallmouth bass anglers are pretty upset.”

Gilliland makes a fair point by noting that bass fishermen share natural resources with anglers of various preferences. So, while the notion of adding gobies to the local lake might sound enticing the long-term implications (not to mention the short-term legal consequences) could be environmentally tantamount to opening Pandora’s box.

“As it is with any invasive species, the risk (of introduction) is just too great,” Gilliland said. “Some people think, ‘If they’re great here, let’s put ‘em everywhere.’ That’s the wrong kind of thinking because we don’t know what will happen in other places. We want to be careful because there could be some bad consequences.”

All things considered

Science is about facts, not feelings, but Tufts describes his outlook for the eastern Lake Ontario/St. Lawrence River fishery as a bright one. Fisheries managers will continue to monitor goby impacts, while anglers must share the responsibility for protecting this magnificent smallmouth factory.

“Like many situations, the more knowledge we have, the more information we have, the better our chances of doing the right things,” he said. “There’s been a lot of science in recent years on bass, gobies and what’s going on in the Great Lakes; and with what’s going on with live release tournaments and how to do things better.

“Gene (Gilliland) and I talk a lot about what can be done by tournament anglers to make sure they’re having a minimal impact on the fishery. In their hands are the best, biggest fish in the fishery, so it’s important that they do their job and release them in the best condition that they can.”

Tufts said he’s encouraged by an increasing emphasis (beyond tournaments) on the value of releasing trophy fish.

“There are still examples of badly run events, but there are more and more well run events and there is more and more education among anglers,” Tufts said. “We have more knowledge than we’ve ever had and I think people are more willing to do whatever they can to protect this fishery.”

Editor’s note: Continue to part 2