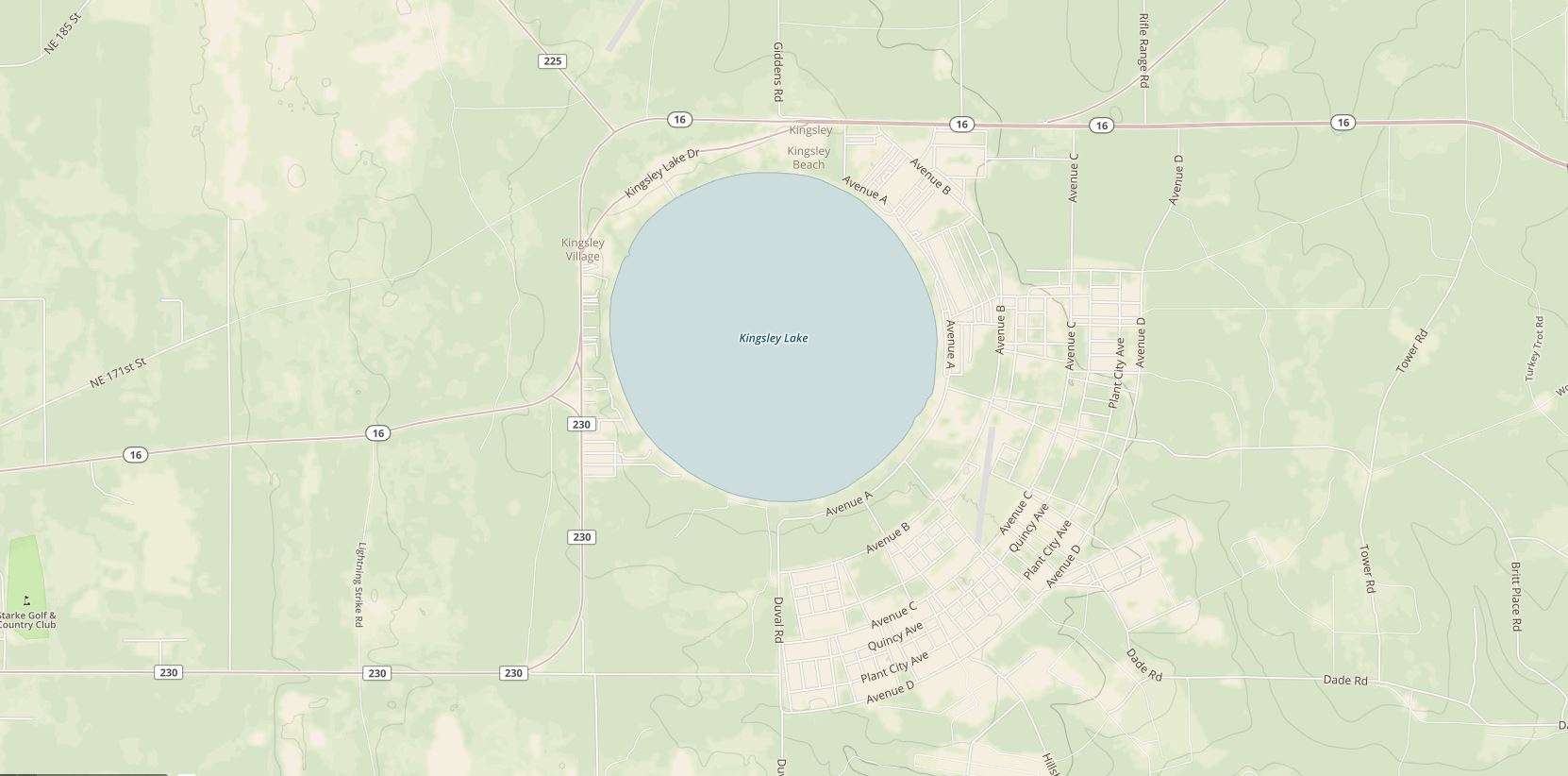

STARKE, Fla. – One of the best bass fisheries that you’ve probably never heard of is 2,000-acre Kingsley Lake in northeastern Florida.

How good is it? During 2015, five of the state’s 10 biggest bass were caught there. Additionally, anglers caught two 15-pound lunkers in one week, including Florida’s largest bass of the year, 15-11. Since 2013, the fishery has yielded 80 bass of 10 pounds or more.

Why is it so good? We don’t know.

But we soon might because of research now being conducted by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), with funding assistance from a federal Sport Fish Restoration Program grant.

Kingsley might never have been recognized as such an outstanding fishery, however, if not for Florida’s innovative TrophyCatch program, which compiled those impressive numbers based on fishermen reporting their catches of bass weighing 8 pounds or more. The program collects information through “citizen science about trophy bass to help the FWC better enhance, conservative and promote trophy bass fishing.”

FWC tagged and released 10 of those TrophyCatch bass, weighing between 9 and 13 pounds, and will monitor those fish through most of 2017. The tags contain both temperature and depth sensors to follow fish metabolic rates and movements in this lake that is far deeper than most Florida bass fisheries.

“In reservoirs known for big fish in California and Texas, there are thermal refuges, which provide a metabolic advantage,” said FWC researcher Drew Dutterer. “Here in Florida, surface water temperatures can reach the upper 90s and even go over 100 degrees on some days.

“When the water is that hot, a bass is that hot as well and its metabolism goes into overdrive, with calories it consumes not going into growth but just to breathe and stay alive.”

In contrast to Toho, Kissimmee, Okeechobee and many other Florida lakes, Kingsley has depths of 40 feet or more in at least 300 acres, with a few places that drop below 80. And as of early July, the tagged fish were spending most of their time at 15- to 20-foot depths, where the water temperature was 65 degrees, compared to the upper 80s and low 90s on the surface. Body temperatures of those fish ranged from the upper 70s to the low 80s.

Dutterer added that the fish seem to stay deeper during the day and move shallower at night, but not enough research has yet been done to determine whether the bass are doing most of their feeding in the shallows.

Based on an examination of stomach contents before those bass were released, though, biologists believe that Kingsley bass eat primarily crappie, bluegill and redear sunfish. “Big bluegills,” the biologist emphasized.

Many Florida fisheries have a more diverse forage base, including shad, chub suckers and golden shiners, he added. But only the latter have thus far been noted in Kingsley.

Another variable that makes Kingsley different is its limited access, with the only ramps at Camp Blanding Joint Training Center. “There appears to be a process for Kingsley Lake property owners to access the Blanding boat ramps,” Dutterer said. “But I believe most boating and fishing there is done by current or retired military personnel who can enter the base.”

But even with restricted access, the biologist added, “it still gets fished pretty hard.”

Bass biology in this rare Florida aquatic environment, however, is what FWC biologists are most concerned with better understanding.

“We’ve collected so much data already because of those telemetry tags,” he said. “But it’s still too early in the game for us to really know what’s going on.”