Bass anglers in the lower Tennessee River are just now learning what boaters in the Illinois River have dealt with for more than 25 years: Boating in waters infested with Asian carp can be hazardous to your health.

“You don’t come to the Illinois River and run a bass boat at 70 miles per hour without a helmet on and a plan for what you would do if a 5-pound carp jumps out of the water in front of you,” warned Kevin Irons, one of the nation’s foremost authorities on invasive carp.

Actually, you can’t truly prepare for that danger, he acknowledged. Irons, who is the Aquatic Nuisance Species program manager for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, has encountered carp at slow speeds, and he once watched a 10-pounder jump out of the water while he was running at 30 mph. It missed him but tore the cowling off his motor.

Noting that silver carp are easily disturbed and will jump as high as 10 feet into the air, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) issued the warning, “With a boat speed of over 20 mph and fish that can weigh over 20 pounds, this can be disastrous. Jumping fish have seriously injured many boaters and damaged boats. Water-skiing on the Missouri River is now exceedingly dangerous.”

Anglers in the recent Berkley Bassmaster Elite at Kentucky Lake presented by Abu Garcia weren’t so much concerned with flying carp as they were the fate of the lake’s legendary ledge fishing. Kevin VanDam calls the Asian carp invasion “the scariest thing facing bass fishing today,” and numerous other competitors in the event expressed similar fears for what once was a world-class fishery.

Television angler Bill Dance of Tennessee was one of the first to sound the alarm, and today he’s among the most vocal in declaring that something has to be done.

“I lived it,” he said of the scourge that has spread from the Mississippi River into connecting waterways. “I’ve seen it from the time it started on the Mississippi. I have seen how our rivers have gone down. I’ve seen our freshwater herring diminish. I’ve seen our threadfin shad and gizzard shad go down. I’ve seen our oxbow businesses go out of business. These nasty things are going to destroy our fisheries.”

Those “nasty things” are bighead and silver carp, which, along with grass carp and black carp, were imported by fish farmers in the 1960s to increase pond productivity and control vegetation and pests. Their introduction occurred in the wake of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, which warned of the dangers of synthetic pesticides. Biologists, including those working for federal agencies, saw the carp as a biological control that was much better for the environment than chemical treatments, according to Irons.

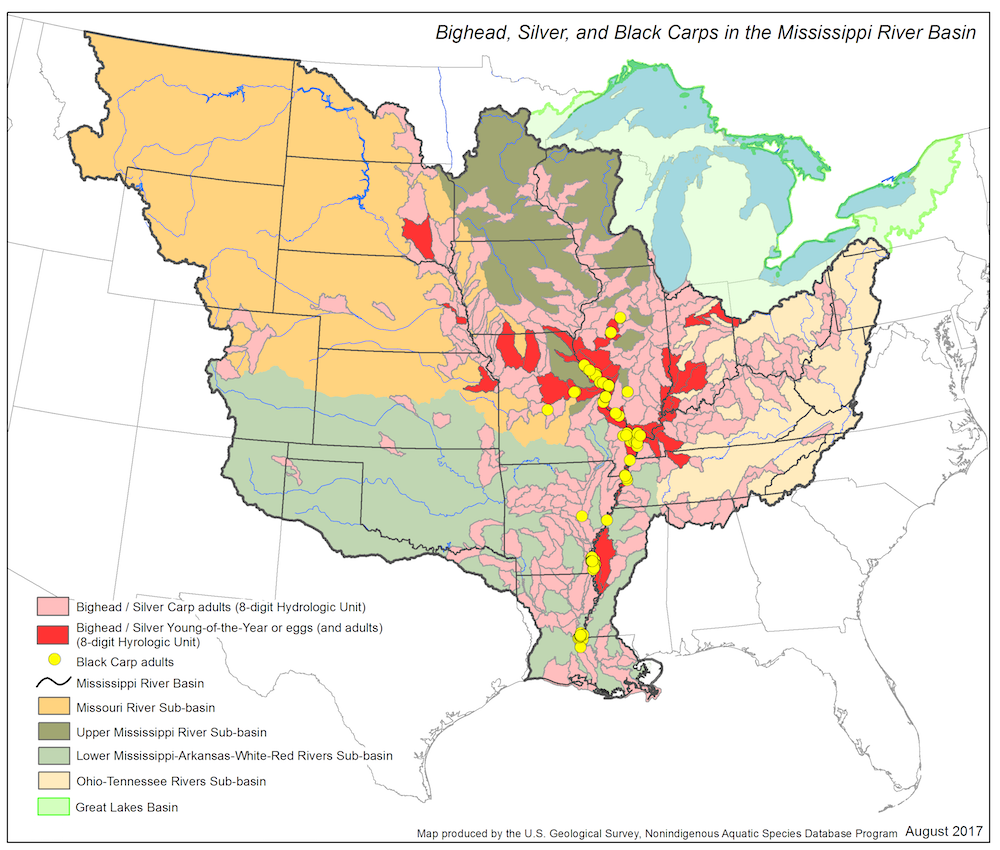

Unfortunately, fish ponds couldn’t contain the carp, and massive floods carried them into the Mississippi River. “These fish got out right away,” Irons explained. “Silver and bighead carp got out in the ’70s.”

With virtually no natural enemy other than a speeding bass boat or predators that carp quickly outgrow, carp spread rapidly up the Mississippi and throughout the Illinois River by the 1990s. Before long, they were threatening to move into Lake Michigan and then into the other Great Lakes.

Among efforts to prevent their escape from the Illinois River, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintains a series of electric barriers near Romeoville, Ill., and that — along with carp removal operations downstream — so far seem to have prevented the unimaginable.

Over the past decade, however, silver and bighead carp have invaded the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, taking up residence in massive numbers in Kentucky and Barkley lakes. Anglers scouting for bass with side-scanning sonar have found ledges and bars that typically teem with bass have now been taken over by carp.

Bighead and silver carp feed on plankton, the same microscopic organisms that sustain threadfin and gizzard shad as well as bass, crappie and bluegill in their early life stages.

“From research that’s out there, the first species that take it on the chin when Asian carp come in are crappie and bass,” said Ron Brooks, chief of fisheries for the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife. “It’s hard to gauge those effects because of the typical up-and-down cycles of bass and crappie in reservoirs, but we’re definitely in a down cycle with crappie and largemouth bass, particularly in Barkley Lake. Condition factors are going down, and that’s a really bad sign.”

His counterpart to the south, Frank Fiss, Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency fisheries chief, agrees.

“We’re a few years into a downturn after a really good four or five years in a row,” he explained. “Local biologists say it was really, really good for a while, so the bar was set very high. Now it’s down low by any measure. We’ve had a really rough winter, with embayments freezing over and all the shad dying and crappie and bass at a low point. All these can bounce back up, but we’ve never been at this point in a lake where we’ve had so many Asian carp before. If things get worse and worse, it will be easy to attribute it to carp.”

Kentucky Lake anglers are already at the point of blaming carp for poor bass fishing. Bill Cooksey, former editor of Midsouth Hunting and Fishing News magazine and currently with the National Wildlife Federation, said he has considered selling a home on the lake that has been in his family for 70 years. He knows at least one bass fisherman from Paris, Tenn., who hasn’t fished Kentucky Lake in a year, instead choosing to drive four hours to fish Lake Guntersville.

The invasive fish now are threatening reservoirs upstream on the Tennessee River. They have used locks to enter Pickwick, Wilson and Wheeler reservoirs upstream from Kentucky Lake, and they’re poised to invade Guntersville, according to Fiss.

He has high hopes for a sound barrier that would be placed near Guntersville Dam. Consisting of underwater speakers, the system emits noise tuned to drive away carp without bothering native fish. It’s been effective in China, where commercial fishermen use sound to herd carp into their nets.

“The technology is being delivered to Barkley Dam this September, where the Fish and Wildlife Service will test it,” Fiss said. “That’s the most carp-abundant spot where they can put this system in and test it. We’re hoping it works.”

Testing of the barrier is set for a three-year period, however, and some biologists fear carp might sneak into Guntersville before a sound curtain is installed there. Then there’s the issue of cost, which might run as high as $1 million, just for Guntersville dam.

Money to deal with the carp issue, however, is in short supply along the Tennessee River.

In July, U.S. Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) inserted language in the Senate Interior Appropriations bill directing the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to focus its efforts on combatting Asian carp in Kentucky and Barkley lakes. The legislation, which cleared the Senate, allocates $11 million to control carp, but that is spread across the entire Mississippi and Ohio river basins.

Most federal expenditures have been concentrated on stopping carp from getting into the Great Lakes. Those electric barriers cost more than $18 million, and estimates for a control plan at Brandon Road Lock and Dam at Joliet, Ill., are running about $275 million.

By comparison, federal funding for carp programs in Kentucky and Barkley lakes have totaled just under $800,000 since allocations began in 2015, said Greg Conover, Mississippi Interstate Cooperative Resource Association coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Kentucky’s Brooks says he has had to spend $4 million in state fishing license revenue to deal with carp on Kentucky and Barkley lakes.

This is a national problem — a national crisis — say Brooks and Fiss, and it will take federal resources and cooperation among the states to deal with it.

“We get a small fraction of the money spent on protecting the Great Lakes,” Fiss noted. “Protecting them is important. People throw out numbers showing that Great Lakes fisheries are worth [$7] billion — but if you look at the value of fisheries in the Southeast and the Tennessee River system, we’re right up there.”

In western Kentucky, including the state’s portion of Kentucky and Barkley lakes, sportfishing alone generates $1.2 billion in economic value, according to McConnell.

Fisheries leaders don’t begrudge the money spent on protecting the Great Lakes, but they do want other river systems, such as the Tennessee, to receive the attention they need.

“The Great Lakes and their connectivity to invasion sources has been a focus area for excluding Asian carp effects,” added Mark Rogers, a research biologist for the U.S. Geological Survey and leader of the Tennessee Cooperative Fish Research Unit. “In the Southeast, we have Asian carp that are established [and we have] important fisheries, and concerns for our fishery resources. We are starting to get the attention of Congress for population controls and monitoring.”

Fortunately, controlling carp in Southern rivers and reservoirs may be cheaper than keeping them out of the Great Lakes. In fact, control efforts might someday become a self-sustaining industry and a boon to beleaguered local economies.

“I wish there were a silver bullet for getting rid of these fish,” said Irons, who has been on the front lines of the war on carp almost as long as anybody. “It’s going to take hard management — targeting and removing them in large enough numbers to protect our crappie and bass.”

In portions of the Illinois River, commercial fishing has reduced Asian carp populations by 50 to 75 percent, according to Irons, and Kentucky’s Brooks is optimistic that, given enough money, similar success can be achieved in the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.

At press time, Brooks was on the verge of signing contracts to finance a fish house near Kentucky Lake and provide incentives for commercial fishermen to remove 5 million pounds of carp per year from the fisheries.

“If commercial fishermen have the incentive and the ‘gears’ [equipment and technology], they can overharvest anything,” Brooks said.

Brooks and others say there is plenty of demand for Asian carp, including from school systems in California, a purse manufacturer in Australia, cement companies everywhere and even fish markets in China.

The challenge is getting the fish in good condition to fish processors. That’s why Kentucky is investing in moving those facilities close to the fisheries, allowing commercial fishers to spend more time fishing and less time trucking.

“This could be a win-win if this industry gets started,” said Brooks, explaining Kentucky’s investment of $1 million in state funds for incentives and forgivable loans. “Now, we’re getting a very nutritious fish — the least contaminated and most nutritious fish we have, other than salmon — and they taste like crappie.

“In a perfect situation, we get this fish house moving so processors are meeting their goals; we get the barriers up to contain them; and we fish them down in Kentucky and Barkley lakes. If we get the extra money from a federal grant of some sort, we [might be able to] eradicate them or get them down to such levels that they can’t reproduce, which is the most crucial thing.”

Brooks and others are counting on a lot of “ifs,” and most hinge on federal support.

“We can’t get this done without incredible interstate resources,” added Fiss, “and we can’t take care of these carp without federal dollars.”

Thanks in part to the Elite Series tournament and other recent events on Kentucky Lake, as well as crusades by Dance, Lyons County Judge Executive Wade White and others, high-profile anglers have mobilized to call for more federal intervention. And it’s starting to pay off, as evidenced by McConnell’s legislation and by congressional briefings held in Washington, D.C., and Kentucky in late July.

Dance is emphatic that the sportfishing industry must join the fray in a big way. In an interview on the floor of the recent ICAST sportfishing trade show, he said, “This industry right here had better quit worrying about how pretty they can make their shirts and how many ball bearings they can put in their reels and start putting some dollars into solving this, or our fisheries are going to be destroyed.”

B.A.S.S. Conservation Director Gene Gilliland believes bass anglers, too, have a responsibility to campaign for a solution.

“From all accounts, we are at a tipping point with the Asian carp invasion,” said Gilliland. “Biologically, they are on the brink of making their way up the Tennessee River into even more iconic bass fisheries like Guntersville. But we are also on the brink of passing legislation that can start to control the invasion.

“If anglers don’t raise their collective voices with Congress, the scales will tip in the wrong direction. We need every bass angler who has ever fished the Tennessee River, or thought about doing it in the future, to contact their elected officials and demand that they support efforts to control Asian carp.”

“I’m a silver-lining kind of guy,” added Rogers. “The fact we have congressional briefings coming to Barkley Lake, and these incentives to commercial fisheries and testing the barriers … is encouraging.”

If those tactics work and carp populations are reduced significantly, Kentucky Lake anglers like Cooksey will be overjoyed. “If we get them down by 80 or 90 percent, we’re golden,” said Cooksey. “That’s about where they were 10 years ago.”

Garry Mason is optimistic, too. The coach of Bethel University’s college bass fishing team and a longtime guide on Kentucky Lake, Mason is afraid of what carp can do to bass fishing — and he’s equally concerned about their effects on tourism, the lifeblood of his region.

“People need to learn to fish around them,” Mason said, noting that tournament weights on Kentucky Lake are comparable now to what they were a decade ago.

“I don’t want to scare anyone off from coming here,” he continued. “But I do want everybody to realize that we have a problem. We as conservationists owe it to our children and grandchildren to deal with the problem now, rather than leaving it for them or someone else to face.”