Like people, bass experience mood swings. Even though they are predatory and considered opportunistic feeders, there are times when nothing seems to tempt them.

Depending on the situation, they may be in a negative, disinterested mood. Other times they can be super aggressive. To further complicate matters, those moods can change from one minute to the next.

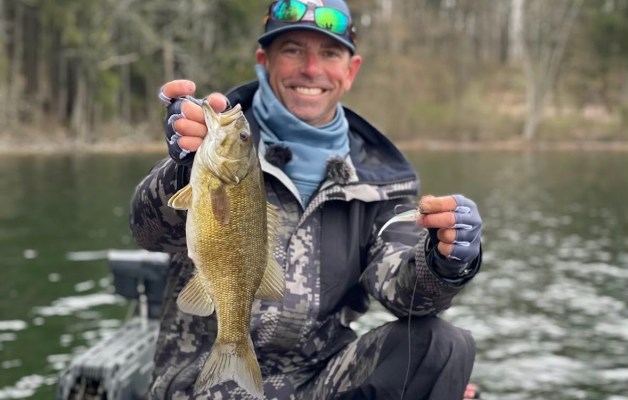

Never was that more apparent than during this season’s Elite Series event on the St. Lawrence River, where big smallmouth were the target. It seemed each day of the competition brought changes in the way the fish would react to various lures and presentations … sometimes even hourly.

I believe a variety of factors influenced those moods swings — including changes in the weather, wind and current velocity, boat traffic and especially angling pressure.

Case in point

The first morning of competition, I drew an early number and was able to reach my starting spot ahead of any other competitors. When I made my first cast, I hooked up immediately. As I played that first fish closer to the boat, I could see several others of the same size, swimming alongside. They, too, were in the mood to feed.

Minutes later, Brandon Palaniuk showed up with a camera boat in tow. Then Seth Feider, and eventually Cory Johnston. That’s when the fish turned from an aggressive mood to a completely defensive posture.

The spot we were fishing during competition was only 4- to 5-feet deep and gin clear. And most of the fish were in a 75-yard stretch. When you put four of the best smallmouth fishermen on tour within those confines, plus two camera boats … well, I think you get the idea.

What could have been a feeding frenzy suddenly turned into game of cat and mouse … with the mice winning.

After a few hours of throwing at fish that weren’t in the mood to bite, Brandon, Seth and Cory all left. And as things slowly settled back down, I was able to fool some of the bigger fish by downsizing my tackle and making lengthier casts.

Bigmouth blues

Largemouth, too, display radical mood swings. The Elite tournament held on the Harris Chain of Lakes back in February, serves as a perfect example.

On Day 1 of the competition, I went to an area that produced a number of easy bites in practice and, for whatever reason, those fish were completely shut down when I returned. Because of poor visibility, I wasn’t able to see them, but I knew they were there. I tried lighter line and slowing my presentation, but it wasn’t until midafternoon when those fish finally began to fire. And the later it got, the better their size.

Looking back, I think it was simply a matter of letting the water temperature warm.

Oftentimes a few degrees can make a huge difference, especially during early spring. And no other subspecies of black bass is affected by temperature change more than Florida-strain largemouth. It’s why our state became the proving ground for “dead-worming.” The bite is sometimes so slow, soft plastics are best served at glacial speed.

That same scenario continued throughout the remainder of the competition … at least for me. Perhaps it was specific to certain fish and what phase of the spawn they were in. The anglers that found postspawn feeding fish experienced an early, aggressive bite using moving baits. Those that concentrated on spawners had to be slow and meticulous with their presentations, and wait them out.

Mood swing summary

So the next time you’re on the water and the fish aren’t cooperating, consider the conditions and how it might affect their mood.

Is the weather stable? If so, then water temperature may not be the issue. Instead, it could be a multitude of other reasons — like current, or lack of it, a sudden change in water clarity, or maybe fishing pressure. Any of these factors could require changing your approach — such as downsizing your tackle, slowing your presentation and/or putting some distance between you and the fish.

Follow Bernie Schultz on Instagram, Facebook and through his website.