Editor’s note: Since this column was written, north Florida has been subjected to heavy rainfall from Hurricane Debby.

Recently, Bassmaster Magazine ranked the Top 10 Bass Lakes of 2024, and among them was Orange Lake in North-Central Florida. In fact, the lesser-known fishery ranked third on the list, and for good reason — it produces countless trophy-size bass each year, many weighing in double digits.

Orange is one of my favorite lakes. It’s where I cut my teeth in competitive fishing, and where I learned countless tactics for catching stubborn Florida-strain bass.

But that was then, and this is now … and Orange Lake could be in trouble.

During the week of ICAST — our industry’s largest trade show — the lake’s water level began to recede at an alarming rate. What was roughly 12,500 surface acres of prime bass habitat is now considerably less than that.

Productive areas of the lake that normally register depths of 5 to 6 feet are now at 3. With that, expansive fields of submerged vegetation are now matted over and look like a golf course.

Bordering Alachua and Marion counties, Orange Lake is managed by several agencies — including the Florida Wildlife Commission (FWC), St. Johns Water Management District and various other state, federal and county agencies. Each is charged with specific components, such as fish management, plant control, hydrology studies, etc. And at this time, it’s unclear if there’s a plan of action.

The lake’s anatomy

Unlike many of Florida’s natural, spring-fed lakes, Orange Lake relies largely on rainfall runoff to maintain a normal pool level.

Located approximately 20 miles southeast of Gainesville, it serves as a collection point for other bodies of water within the Orange Creek Basin. To the north is Newnans Lake, which drains into Prairie Creek, then on to Orange Lake at River Styx. To the east is Lake Lochloosa, which feeds Orange via Cross Creek.

At its southern boundary, Orange Lake drains to Rodman Reservoir, which in turn connects to the St. Johns River. So, as you can see, it’s a complex system — the majority of which relies on annual rainfall for adequate flow and depth.

Orange Lake is considered eutrophic. It’s generally shallow with a maximum depth of 12 feet. Its bottom is soft, comprised mostly of muck-like sediment, which supports massive fields of vegetation — both emergent and submerged. Among the different varieties are joint grass, lily pads, arrowheads, hydrilla, dollar weed, hyacinths and others.

There are also floating islands (or tussocks), some of which are quite large. They form from layers of substrate that become buoyant and rise to the surface, then serve as rafts for a multitude of terrestrial plants, even trees.

In all, Orange Lake is a veritable salad bowl. And that’s precisely why it’s such a productive fishery. But without adequate water levels, the bulk of that greenery is rendered useless.

Then and now

In 1956, a large sinkhole opened in the southwest corner at Heagy-Burry Boat Ramp and it literally drained the lake. Reportedly, they dumped auto bodies and countless yards of concrete to plug the vent. And apparently it worked, at least for a time.

Other drainages occurred in 1998, 2011 and 2017, all of which resulted from extended periods of drought. But that hardly seems plausible this time. Over the past two years, North Florida has experienced copious amounts of rainfall, easily exceeding the norm. And that subsequent runoff flows freely into Orange Lake and beyond.

So what’s the cause this time? Could it be from consumption?

North Florida’s increasing population gets the bulk of its water from the aquifer — an underground network of streams replenished by groundwater seepage. As the number of residents increases, more and more demand is placed on that resource.

In the simplest of terms; too many straws are siphoning off a limited supply of pure, potable water — including commercial consumption from agriculture, industry, even bottling companies who sell the precious resource for profit.

According to FWC Regional Administrator, Allen Martin, that’s not the case … at least not the main reason. He feels it’s the result of a late-spring drought that extended into the summer months. And in his opinion, it could be a good thing.

“Fluctuating water levels can stimulate fish populations and produce big fish,” claims Martin. “Orange Lake is a prime example. The spike in trophy fish we’re experiencing now is believed to be the result of a drought that started in 2017.

“Several things can happen during periods of drought. Sediments oxidize and compact, which in turn firms up the substrate, and that’s good for the overall health of a lake. As water levels pulse back up, so do fish populations … especially under higher water levels. But if the drought persists, it can be detrimental and prolong the recovery of a fishery.

“Rodman Reservoir is another good example,” he continues. “Every few years, the lake is drawn down to firm up its bottom composition. Many people believe it’s done for weed control, which can be a side benefit, but it’s more about maintaining sediments.

“As a result of those drawdowns, fish populations spike. You see it on Texas lakes, like O.H. Ivie, Fork and others … places that consistently grow trophy bass in big numbers.”

Apples to oranges

Whether it’s from lack of rain, consumption or a combination of the two, Orange Creek Basin has a long history of dramatic fluctuations in water levels, and each time the lake has recovered.

For those of you planning to visit Orange Lake in the near future, it might pay to keep a watchful eye. Although area ramps are still accessible, there’s no guarantee that will be the case in the coming weeks or months.

The National Weather Service is predicting an active season for tropical storms. If accurate, that should bring what Allen Martin terms “named rains” — that is, rainfall from named tropical cyclones. And with that, the entire Orange Creek Basin should replenish itself.

Only time will tell.

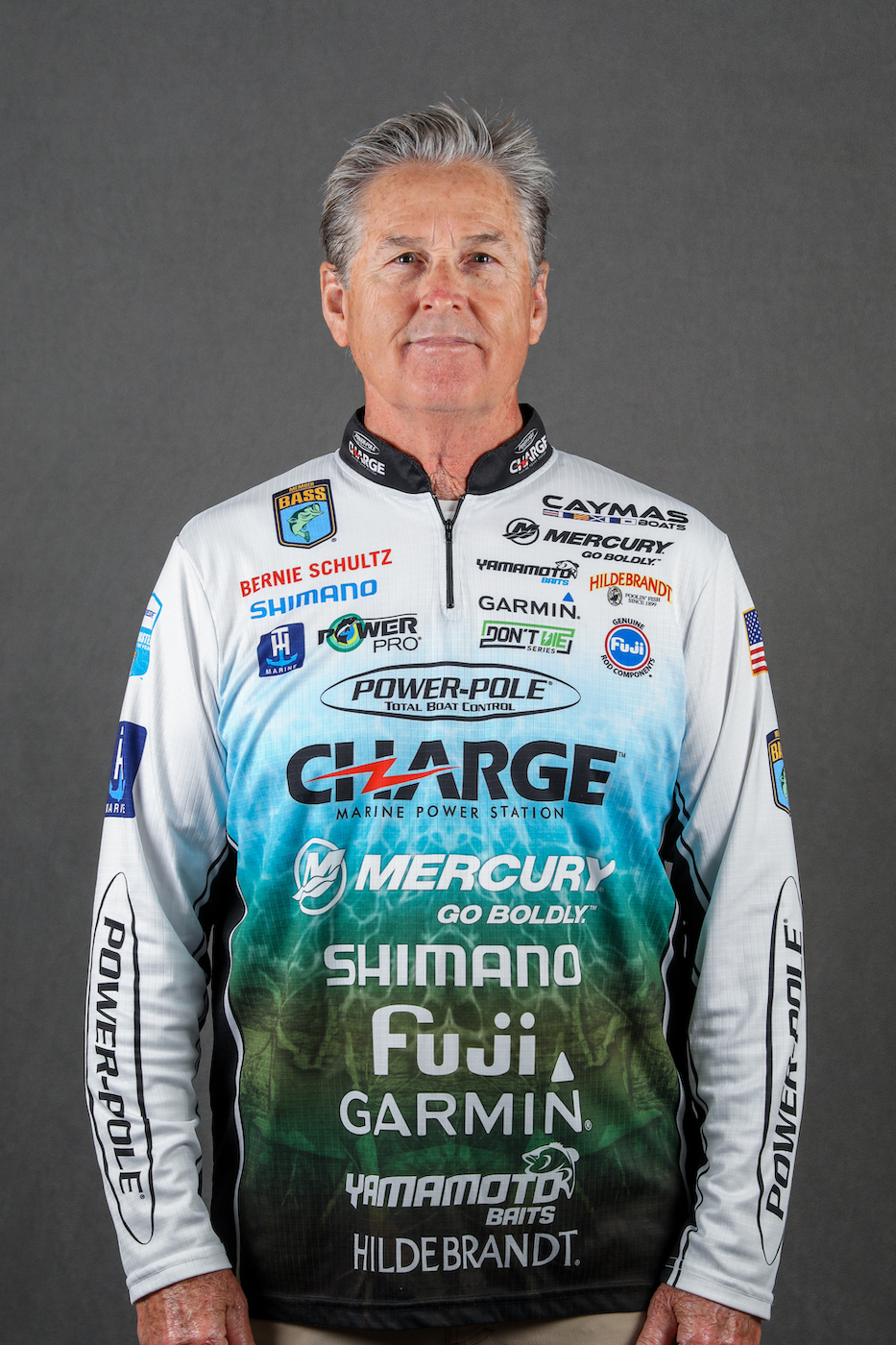

Follow Bernie Schultz on Instagram, Facebook and through his website.