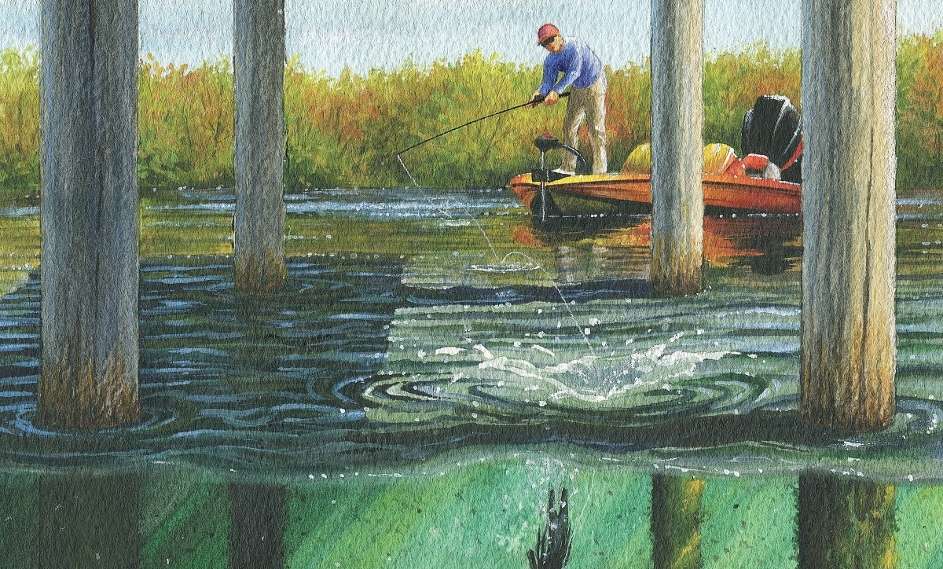

Skipping a jig with baitcasting equipment is not easy. But learning this trick — and knowing exactly where to employ it — will make you a more successful bass angler

On Kentucky Lake, you’d better be able to find fish on ledges if you want to be competitive. In Florida, you have to be able to flip grass. On Lake Erie, drop shotting and tube dragging offshore structure are the keys to success. On the lakes of North Carolina’s Catawba River chain, though, if you can’t skip a jig into the deepest crevices of a dock’s caverns, you might as well give up now.

“Ninety-five percent of winning bags on lakes like Norman and Wylie have at least one fish that came off of a dock,” two-time Bassmaster winner Andy Montgomery says. “And usually it’s more than half of the fish. That’s where they live.”

While that simple fact has given rise to legions of Carolina jig skippers, it applies anywhere there are docks, from California to Lake of the Ozarks to the far Northeast.

“If you really work at it, it’s almost an art,” Elite Series pro Britt Myers says. “A lot of people are intimidated by it, but if you just spend some time on it, the whole process becomes second nature.”

While putting a jig into a dock’s darkest recesses is often compared to “skipping a flat stone,” a jig has more to “catch” the water’s surface and therefore requires more finesse to be precise and also avoid backlashes.

“A lot of people think it’s sidearm, but it’s more of an underhand cast,” Montgomery says. “You want to start it at a 45-degree angle to the water so that when you release the line, it’s right at the surface of the water. It’s all about practice. You need to go to the lake with two rods, a sack of jigs and some chunks.”

With time, not only will you be able to get it under the docks, but you’ll also be able to control the number of skips and the length of your cast, so the lure falls in the preferred strike zone. Montgomery says you generally want the jig to get as far under the dock as possible, but not go so far as to skip out the backside.

Casting angle is critical, because it allows you to get a jig in front of the fish and it determines whether you’ll be able to get a hooked fish to the boat. If possible, you should plan for a clean exit strategy, but there are times when a dangerous skip is the only option, meaning you may have to pull a bass over crossbars or around poles.

“Pay attention on the fall,” Myers says. “If he runs 10 feet and wraps you around a pole, you may not get him in. You need to set the hook quick and crank him out of there.” Sometimes, though, losses are part of the game. “I like to think that if you make a high-risk skip and end up losing that fish, you have to live with that. If you hadn’t taken a chance and skipped it in there, you were never going to catch that fish anyway.”

The perfect jig

While just about any leadhead jig can be made to skip, using one tailored to the technique makes the process much easier.

Montgomery uses a locally made 1/2-ounce jig from Shooter Lures that features a hand-tied skirt and an Arkie-style head. “That weight-forward design makes it skip a little better,” he says.

Myers prefers a 1/2-ounce War Eagle Flipping Jig.

“I don’t care if it’s 6 inches deep or 20 feet deep,” he explains. “I can put a 4-inch Chigger Craw on the back and that thing skips a mile. Even in 6 inches of water, big bass like that quick fall. It triggers bites. The reason I always use the same weight jig is for the consistency. A lot of guys might switch to something lighter or heavier, but when you pick up a different lure, the dynamics of the cast have to change.”

For a trailer, Montgomery uses a Strike King Rage Bug 90 percent of the time. “You thread it on that hook and it’s pretty flat, so it skips well,” he says. The other 10 percent of the time, he’s likely to use a standard pork chunk, generally when it’s cold. Myers finds himself reaching for a Berkley Chigger Craw most often.

“I don’t get into colors too much,” explains Montgomery, who says he almost always relies on some shade of brown or green pumpkin. Myers uses more colors, but not many. “If it’s clear to stained, I’ll use green pumpkin, green pumpkin orange or brown and orange,” he explains. “If it’s more heavily stained to muddy, I like black and blue, and if it’s extremely muddy, I prefer straight black.”

Tackle choices

Montgomery believes that there is no one-size-fits-all rod choice for skipping because all of our arms are different distances from the water’s surface.

“I’m 6 feet, 4 inches, so I like a 7-foot, 1-inch or 7-foot, 2-inch medium-heavy rod with a fast tip,” he explains. “I call it an 80/20 action, with the top 20 percent having some tip to it.”

He pairs it with a Daiwa Tatula baitcasting reel and encourages would-be skippers to “become really close friends with your thumb.”

“There are two controls on that reel: the traditional knob on the right side of the reel and the magnetic control on the left side. Mine are extremely loose, but when you’re still learning, they should be fairly tight, with the magnetic all the way up. Eventually you can lower that. Both of mine are set at about halfway on both sides.”

Myers, who relies on a Pinnacle baitcasting reel to avoid backlashes, stresses that the 7.3:1 gear ratio is key to his success.

“I skip it up under the dock, hop it once or twice and then reel it in and skip again,” he says. “They’ll generally pick it up when it’s falling or when it first lands in front of them on the bottom. Then I move on.”

While beginners might want to use monofilament because it is a bit more forgiving and backlash-resistant, eventually both pros moved on to fluorocarbon — Seaguar InvizX for Montgomery and Berkley Trilene 100 Percent for Myers.

The perfect dock

The best docks vary from one waterway to another, and from one season to the next, but on any fishery with lots of them, it’s often possible to pattern bass on a given day.

“They might prefer pole docks or foam floating docks or docks on a point or docks in the back of a pocket,” Myers says. “Once you figure that out, sometimes you can even narrow docks down to a single cast.”

No matter what the season, Myers said that many of his most productive docks are either by themselves in an area or stick out in some way.

“There may be 20 docks on a stretch and one sticks out farther,” he says. “That’ll often be the best one.”

A bit of brush can be good, enabling a knowing angler to predict the strike zone, but Montgomery warns that there’s such a thing as too much brush. It may attract fish, but it spreads them out and makes getting a clean cast in and a hooked fish out more difficult. Myers said that in the late winter and early spring, he may target brush exclusively, but as the year progresses, other dock elements may hold the fish; for example, in the summer, shade lines may be critical, and in the spring, the bass may use the poles to spawn.

It’s long been conventional wisdom that older docks are most productive because they grow algae, which attracts baitfish, which attract bass. Montgomery used to subscribe to that notion, but he’s seen productive ancient docks on his local lakes torn down and replaced, and “the new ones are usually just as good.” That has led him to believe that location trumps all other factors.

“In the spring, I like one on a point leading into a spawning area,” he says. “Really shallow, like 2 to 3 feet deep, with a walkway leading to a big black float, which I believe holds a little bit more heat. In the summer, I like one that’s a little bit deeper, up to 15 feet, and close to some type of creek channel, with scattered brush.”

Myers likes those same docks, but he also bucks the trend on some occasions. “Some of my friends are going to kill me for saying this, but in the heat of summer on Wylie and Norman, I like some of the shallowest, flattest docks you can find. They often hold the biggest fish.”

Dock strategies

Neither pro is likely to spend hours on a single dock. In fact, their preference is to make a few key presentations and then move on.

“Unless it’s a massive dock, I really make very few casts,” Montgomery says. “Usually two or three. I don’t try to go in each hole because basically they’re all going into the same place, anyway.”

Similarly, Myers recalls situations where he knew exactly where the fish would be lying if they were there — perhaps the shaded part of the walkway or the front of a boat stall — which enabled him to “narrow docks down to one cast.”

In some locales, like tidal rivers, docks will “reload” with bass as the day goes on. Other fisheries, however, are “one and done.” Once you’ve caught a fish from one, move on and find another. “If I fish a boat dock pattern in a tournament, I don’t depend on them reloading,” Myers says. The best days to skip docks are usually when it’s sunny and slick.

Montgomery says that a little bit of wind actually helps because it makes the fish feel more secure, but flat conditions take away techniques from other anglers, putting those who can’t skip docks at a severe disadvantage.

Wherever you fish for bass, docks will hold fish at some point in the year, if not all of it, and a jig is usually the best way to extract the biggest specimens. Unlike when fishing down a bare bank or a mile-long ledge, the fish that are there are essentially pinpointed, and for the most part they’re catchable. That doesn’t mean they’re easy to get to, or easy to extract, but it does mean that the presentation is every bit as important as the hunt.“When he lives under that dock, he feels protected,” Montgomery says. “You just better have a good relationship with your thumb and the Lord.”

Originally published in Bassmaster Magazine September/October 2015.