“The scientific history of the Black Bass is a most unsatisfactory one.”

Those are not our words as the authors of this three-part story for Bassmaster Magazine. Those are the words of James A. Henshall, and they are the very first words in the very first chapter of his legendary Book of the Black Bass, first published in 1881.

A lot of science has happened since then, and the Micropterus genus (black bass) has been the focus of a fair amount of it. But in recent years, all that attention has created a confusing and perhaps untenable scenario for largemouth bass anglers in pursuit of America’s, and the world’s, most popular gamefish.

To get a picture of what’s happening now, it helps to look back at where we’ve been … way back.

Shortly after the American War of Independence, French naturalists combed North America, attempting to catalogue new species of fish based on their physical appearance. These naturalists often unknowingly worked with what Henshall described as “uncertain and inaccurate” material. As communication at that time was obviously slow, two scientists could work independently on the same thing for years and never know it. The black bass we know and love were first scientifically described in this manner in the early 19th century.

Poor materials and communication led to many black bass being given different scientific names even though they were actually the same species. In modern science, it’s really important that a species gets one name to avoid confusion. Back then, the largemouth bass could be described as Labre salmoides (“trout-like”), Huro nigricans (“black huron”) and Micropterus floridanus among many others. To make matters worse, damaged samples could lead the largemouth bass to be confused with a different black bass species entirely. Hindsight being 20/20, it was a mess, and if you really want to make your head spin, you should check out the first two chapters of Henshall’s book.

Ultimately, Henshall drew a line in the sand and pegged largemouth bass as what we have known as Micropterus salmoides. A separate strain of largemouth known as the Florida bass (Micropterus salmoides floridanus) was described in the 1940s by Bailey and Hubbs, and that’s where things have sat … until now.

Splitters And Lumpers

If you think live, forward-facing sonar is a technological leap in the world of fish and fishing, know that DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) testing has been at least as impactful in the world of taxonomy and conservation. DNA is the molecule that carries genetic information within an organism. Taxonomy is the science of classification.

As DNA technology has advanced, our ability to identify small but perhaps vitally important differences in animals has grown by leaps and bounds. A fish in one river may not be discernibly different from a visually identical fish in another river just a few miles away. In fact, it may be so different that scientists deem them worthy of special classification or meriting a new species designation.

Why? Well, scientific advancements allow us to better understand the differences between groups of fish and apply that knowledge to management practices. In the case of conservation genetics, this “splitting” helps to protect unique populations. Think of Florida bass in Florida. Without genetic knowledge and good management practices, we could dilute or otherwise undermine a population generally recognized as having the best potential for trophy size.

We’ll call the conservation scientists who pursue such taxonomic differences “splitters.” On the other side of the aisle are the “lumpers,” who see little or no need to recognize differences in fish that cannot be seen with the naked eye.

And that’s the battleground in a nutshell.

The American Fisheries Society

The American Fisheries Society (AFS) was created in 1870 and is dedicated to advancing science and protecting fisheries resources. It has more than 8,000 members, mostly fisheries managers, biologists, professors and ecologists, and AFS is a driving force behind the recognition and naming of fish species not only in the United States, but across the globe.

In 2023, AFS published the eighth edition of Common and Scientific Names of Fishes from the United States, Canada, and Mexico. For the first time, “largemouth bass” (formerly “Northern bass” or M. salmoides) and “Florida bass” (formerly M.s. floridanus) are listed as separate species. The new designation is based on a 2022 Yale University paper on black bass that determined new genetic standards and ranges for black bass species. This included extending the range of Florida bass to areas in south Georgia and the coastal Carolinas. Everywhere else, except for a thin strip through north Georgia and the inlands of the Carolinas, bass populations are largemouth. That thin strip in the middle is a zone of natural hybridization or mixing of Florida and largemouth genes (keep that in the back of your head).

With new species come new names. To figure that out, AFS went back to some of the earliest names. Florida bass are now known as M. salmoides, which means a new name is needed for everything else. The Northern largemouth is now M. nigricans. Those French naturalists got the naming honors after all!

The Record Books

Since the late 1970s, the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) has been the primary oracle for freshwater fishing records. The IGFA took over the work of Field & Stream magazine, primarily conducted through its annual fishing contest, which ran from 1911 through 1977.

To its credit, the IGFA is a steward of sportfishing with a long history of support and involvement within the industry. The IGFA also works to stay on top of many scientific advancements that are driven by AFS. This includes conservation initiatives based on recognizing new species.

Sometimes the new distinctions are not a problem. But we’re talking about the largemouth bass here — the most important sportfish in the world.

Earlier this year, the IGFA announced it would follow the recommendations laid out by the 2022 Yale paper and make adjustments to records for black bass. Specifically, the Florida bass and the largemouth bass would become two categories, with the largemouth bass maintaining the 22-pound, 4-ounce all-tackle world record. This has left the Florida bass open for a world-record chase. Oh, and any new competitors for the all-tackle world record must be genetically certified.

This poses all sorts of questions: What of the world records? The largemouth bass — the most sought-after gamefish in the world — is now split. The largemouth bass (M. nigricans) record — perhaps counterintuitively — belongs to George Perry and Manabu Kurita, just as the old largemouth record did.

A new Florida bass world record has been certified by IGFA out of Texas at just 15 pounds, 13 ounces. Does anyone believe that should be the standard bearer?

And what of the hybrids? Currently, IGFA does not recognize a world-record bass that is neither a “pure” Florida nor a “pure” largemouth, even though such hybrids occur naturally.

Can you positively identify Micropterus salmoides and Micropterus nigricans? What about a hybrid of the two? Unless you have access to DNA testing facilities, the answer is a hard no.

And who’s capable of conducting those tests? What standards should be used — IGFA standards, state standards, university standards, private lab standards? Who will pay for this testing? Will state record-keeping organizations line up behind AFS or IGFA in their species classifications?

If an angler — especially an avid, experienced angler — cannot tell the difference between two fish without a DNA test, should there be separate records for those species?

Should the records serve scientists or anglers? The splitters are carrying the day with conservation, but shouldn’t the lumpers prevail when it comes to the records?

And what if — stay with us here! — what if we had DNA from Kurita’s 22-5 bass out of Japan in 2009 that proves his giant had Florida genes? What might that do to the apple cart?

The mind boggles.

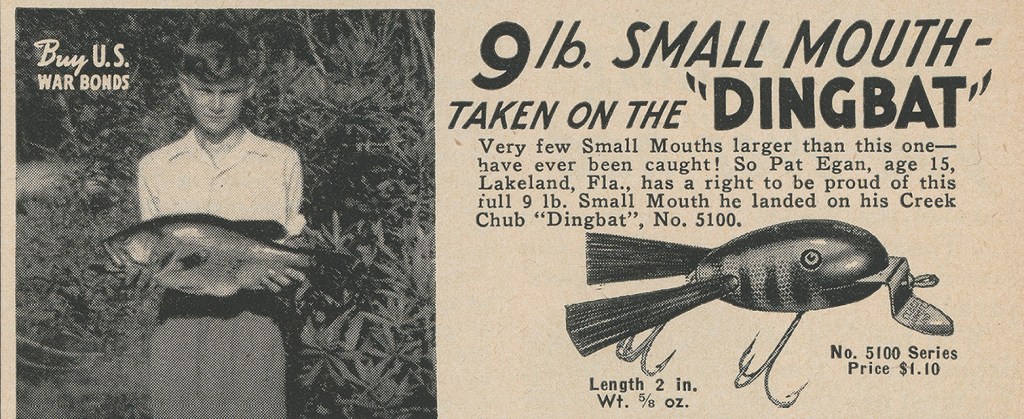

A Cautionary Tale: Florida’s World-Record Smallmouth

What happens when the science gets so confusing that even scientists are confused? Welcome to the cautionary tale of Florida’s world-record smallmouth bass.

That’s right … Florida.

Smallmouth bass are not native to Florida, but they were stocked in the Sunshine State several times beginning in 1908. So, when lunker “brown bass” started popping up, few were surprised.

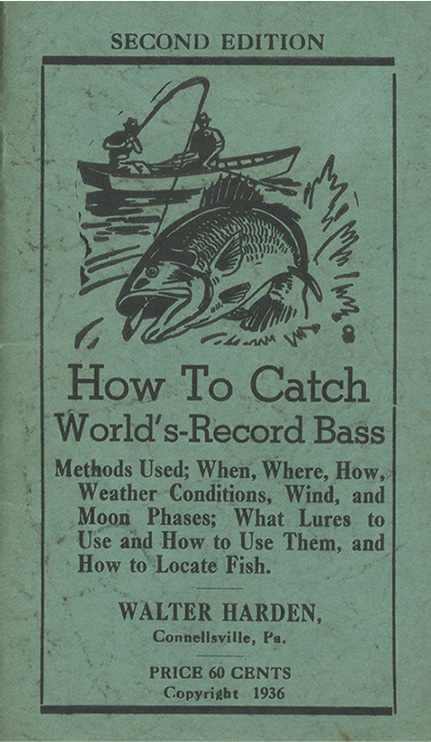

By the 1930s, some of these fish weighed in the teens, and in 1932, a Pennsylvania angler named Walter Harden held the world record at 14 pounds. He even wrote about his prowess at catching big smallmouth in How to Catch World’s-Record Bass.

Of course, the problem was that there were no actual smallmouth bass in Florida. None of the stocked fish survived or propagated in the tropical climate, and the “smallmouth” were actually largemouth that met the scientific parameters that defined the smallmouth bass at that time (i.e., a certain range of dorsal spines and lateral line scales). Since smallmouth and Florida bass occasionally overlapped in those particulars, honest scientists and anglers misidentified fish that any modern angler would have spotted a mile away.

It took 17 years after Harden’s record “smallmouth” before all that got cleared up.

Top 10 LMB (according to Bassmaster records)

1. Weight: 22.3108 Angler: Manabu Kurita Date: 07/02/2009 Location: Lake Biwa, Japan

2. Weight: 22.2500 Angler: George Perry Date: 06/02/1932 Location: Montgomery Lake, GA

3. Weight: 22.0100 Angler: Robert Crupi Date: 03/12/1991 Location: Lake Castaic, CA

4. Weight: 21.7500 Angler: Michael Arujo Date: 03/05/1991 Location: Lake Castaic, CA

5. Weight: 21.6875 Angler: Jed Dickerson Date: 05/31/2003 Location: Lake Dixon, CA

6. Weight: 21.2000 Angler: Raymond Easley Date: 03/04/1980 Location: Lake Casitas, CA

7. Weight: 21.0100 Angler: Robert Crupi Date: 03/09/1990 Location: Lake Castaic, CA

8. Weight: 20.9375 Angler: David Zimmerlee Date: 06/23/1973 Location: Lake Miramar, CA

9. Weight: 20.8600 Angler: Leo Torres Date: 02/04/1990 Location: Lake Castaic, CA

10. Weight: 20.2500 Angler: Gene Dupras Date: 05/30/1985 Location: Lake Hodges, CA