Rock. In some reservoirs it's the predominant bass habitat. And when that is the case, sorting through the rockpiles, outcroppings, sheer bluffs and other geographical formations can be a perplexing proposition at best.

And then you are faced with types of rock: chunk rock, pea gravel and other terms that bass anglers have given this hard substrate over the decades to describe which kind is best for a certain situation.

With their rocky outcroppings, sinuous creek arms and deep, turquoise-tinted water, rocky lakes are vastly different from the lower South's murky sloughs and the Midwest's natural lakes rimmed with aquatic vegetation, and tidal bass fishing waters from coast to coast.

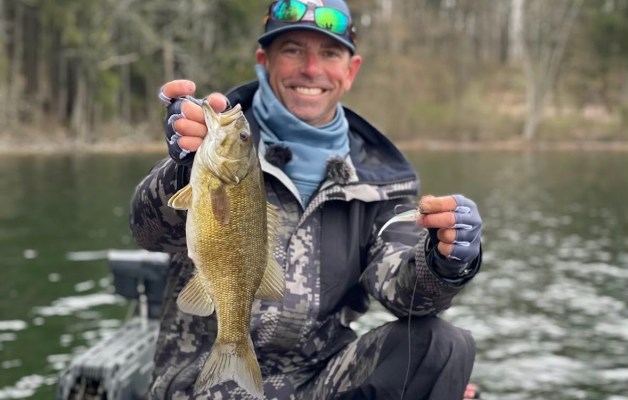

If you are interested in honing your talents for fishing lakes loaded with rock, then read the following tips and tactics from Fred McClintock, a renowned smallmouth angler and guide on Tennessee's Dale Hollow Lake, also where the world record bronzeback was caught. The colorful Pennsylvania native moved to Tennessee in the mid-1980s after taking early retirement from his job as a foreman in a steel mill, and then quickly became one of the most sought-after highland reservoir guides in the nation.

Bass on the rocks

"You're not imagining things if you think bass in rocky lakes behave differently from bass in lakes where wood or weed cover is dominant," states McClintock. "Bass are highly adaptive predators. Just as they modify their behavior to fit their

environment, you, in turn, will have to modify the way you fish if you hope to score in a rocky venue."

McClintock lists some key facts about bass in rocky lakes that savvy anglers can use as the foundation of a successful fishing strategy:

- Cover isn't everything — "Bass in rocky lakes don't relate as strongly to cover as do bass in stumpy or weedy lakes. Rocks aren't nearly as attractive to bass as either grass or wood, probably because bass can't penetrate rocks the way they can bury in grass or wedge between roots or branches. Also, both wood and rocks attract a greater variety of forage species. Obviously, if you do find wood or weeds in a clear, rocky lake, you should fish it, but be aware that bass may relate more loosely to this cover than they will in a shallow, murky environment," McClintock says.

- Deep water = concealment — "Bass in rocky lakes commonly use deep water to conceal themselves from prey and other predators. While you can catch bass in 3 feet of water in a murky lake with abundant grass or wood cover, you may have to fish in 20 feet of water to catch bass from a clear, rocky reservoir."

- Forage possibilities — "Here, bass typically feed on schooling baitfish, such as threadfin and gizzard shad. These species dine on drifting plankton blooms and may travel far offshore — another reason you seldom catch bass in a rocky venue by pounding the banks. Trout are another popular menu item in many rocky lakes; all three species of bass will dine on stocker-size rainbows. Crawfish are abundant around rocks, but they're largely nocturnal in clear water, which helps explain why night fishing can be so effective in a rocky reservoir."

- Structure-oriented — "While cover isn't critical to bass location in most rocky lakes, bass definitely orient to major structures, including points, underwater humps, channel dropoffs and flats. Sparse, scattered cover, such as a patch of grass or an isolated stump, can concentrate bass on large structures."

- Something different — "Every experienced angler knows bass gravitate to something different in their surroundings, but bass in rocky lakes take this axiom to the extreme. Here, 'something different' may mean an apparently insignificant shift in bottom composition from gravel to clay, or a subtle transition from fist- to head-size rock along the bank. Pay close attention to such details, and you'll find bass."

- Suspenders — "Bass in rocky lakes spend a great deal of time suspending rather than hunkering down on the bottom or sticking close to some object, as they often do in other types of habitat. They may suspend directly over a depth change, such as a point, ledge or channel drop; adjacent to a sloping bank or bluff; in open water near a school of baitfish; or in the middle of a tributary. The depth at which bass suspend can be dictated by a variety of factors, including the temperature of the water column, the location of their forage, the amount of light penetration and the level of dissolved oxygen in the water. Most bass fishermen view suspending bass as next to impossible to catch, but as you'll see, there are several approaches you can use that can pay off big."

- Playing the odds

When fishing a rocky lake, McClintock looks for high opportunity scenarios — conditions he knows can generate a major bass bite in a hurry. "The single most important factor leading to active bass in a clear, rocky reservoir is wind," he indicates.

"When it's dead-calm, especially dead-calm and sunny, the bite can be painfully slow. Wind concentrates plankton and repositions baitfish; any time there's a wholesale forage movement, bass sense a feeding opportunity and move into the area."

Wind also triggers bass to move from deep to shallow water. As waves build, they create a band of murky water against the shoreline, which bass often use for concealment when ambushing prey. Wind direction has a definite seasonal impact on bass in rocky lakes, he adds.

"In spring, a south or west wind is best, while a north or east wind can shut 'em down. But in fall and winter, I'll take any wind except an east wind — I've had some awesome days late in the season in a north wind," says McClintock, whose favorite lures for windy conditions include deep diving crankbaits, suspending jerkbaits, spinnerbaits and leadhead grubs.

A sudden influx of warm, murky water can trigger a tremendous bass bite in a rocky reservoir early in the year.

"Seasonal deluges are typical in my region from February through April," McClintock says. "When the lake level jumps up overnight and the heads of the tributaries are running with warm, muddy water, hibernating crawfish emerge in droves, and bass will move in and gorge themselves.

"Chunk bottom-bumping crankbaits and hard-throbbing spinnerbaits in shallow water. Take advantage of this opportunity quickly, however, because rocky lakes tend to clear up fast."

Spawn time can mean excellent fishing in a rocky lake — if you know where to fish.

"Smallmouth and spotted bass spawn earlier than largemouth," McClintock says. "Look for them on gravel flats on the main lake or the first half of tributary arms, often in 8 to 12 feet of water, when the lake reaches the lower 60s in temperature. Swimming a 5-inch chartreuse grub slowly back to the boat will bag a trophy smallmouth or spot. And when the water temp reaches 68 or so, check creek arms for bedding largemouth. They'll nest in pockets along the bank, around sunken wood cover, and in open areas between flooded bushes, and they will eat a floating worm or surface minnow."

The postspawn means water in the mid-70s, and some unlikely bass patterns.

"Smallmouth will slam Zara Spooks and similar surface lures fished at the edges of flats and around main lake points," he has found. "Never mind that your lure might be working over 80 feet of water; a suspending smallmouth will swim up 30 feet to blast it. On rough days, try a willowleaf spinnerbait or soft jerkbait fished out in front of flooded bushes — bass will gather in shallow water to feed before dispersing to their deep summer haunts."

Summer usually means night fishing. If grass is present in the lake, summer is the best time to fish it, McClintock emphasizes. "Early in the season, when the water temperature is still in the low 70s, all species of bass will move onto shallow, grassy humps at night; you'll get your arm broken by slow rolling a heavy Colorado-blade spinnerbait so it just barely ticks the top of the weeds."

As summer progresses and the water warms into the 80s or low 90s, fish progressively deeper weeds. "You'll be amazed how deep grass will grow in these clear lakes," he notes. "I've caught bass from 40-foot grassbeds at Dale Hollow in late August on spider jigs."

Fall can be the most frustrating time to fish a rocky lake, McClintock believes. "A deep, clear lake takes a long time to cool down, so even when the air temperature is downright cold, the lake can be surprisingly warm below the surface layer, and the bass can be incredibly deep," he says. "I've often found bass in early November in 55 feet of water along 45 degree chunk-rock banks. At these extreme depths, metal blade baits, spoons and tailspinners are just about the only lures that will work."

McClintock loves to fish rocky lakes in winter — the colder, the better. "I like the lake to get cold enough to have a shad kill — this usually requires the water dipping down around 42 degrees for several days," he notes. "When you start noticing disabled baitfish flipping weakly a few feet under the surface, try a suspending jerkbait — it's a dead ringer for a dying shad.

"I've also caught big bass in water as cold as 38 degrees on crankbaits, usually when there's a stiff west or south wind blowing. Bass need deep water access in winter; a main lake point that drops into a channel is a good spot to look," he suggests.

Another classic midwinter pattern is vertical jigging "the hollows" for suspended bass. "Hollows are deep, V-shaped tributaries; they're practically featureless," he admits. "But for some reason, they attract giant schools of baitfish and, therefore, plenty of bass. Simply idle toward the back of a creek arm, watch your graph for suspended bait and bass and drop a spoon or blade bait right in their faces."