Editor’s note: As part of the celebration of the 50th anniversary of B.A.S.S., over the next year we will highlight some key players, innovations and events that shaped the organization’s history and the sport as a whole. Where possible, we intend to go back and interview those innovators to find out not only how they came to that status, but also to find out what they’re doing now. Here’s the first of our “Where Are They Now” features.

It may be hard for younger anglers to conceptualize, but for much of the history of B.A.S.S. tournaments there was just one line choice – monofilament. Actually, that’s not exactly accurate because if you looked at the patch vests of competitors in the 80s and early 90s, it might’ve seemed like there were two types of line – Original Stren and Trilene, and just about nothing else. Other brands were more or less outliers, and while fluorocarbon had been invented in Japan in the early 1970s, and some forms of braid had been in existence for decades, they weren’t in wide use among “serious” professional tournament anglers.

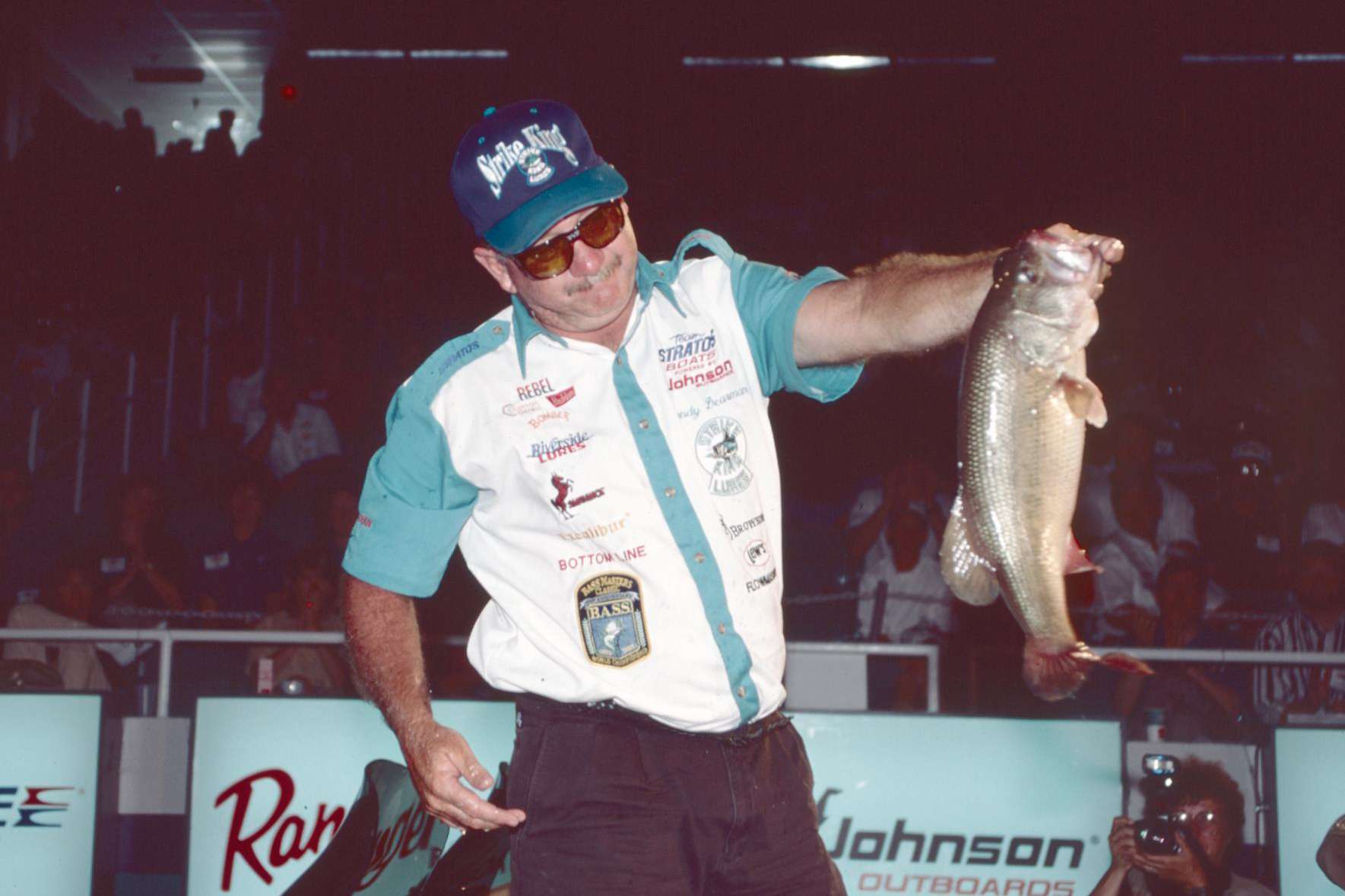

Into that void stepped Texan Randy Dearman. If you use braided line today – for frogging or flipping mats or for anything else – then you likely owe the six-time Bassmaster Classic qualifier a tip of the hat. His record-setting win in the 1993 Bassmaster Texas Invitational was premised on his then-novel use of “Lynch Line” braided line to extract big bass from the thick cover of Sam Rayburn Reservoir.

It took a series of fortuitous circumstances for it all to come together. While Dearman had guided some on Lake Livingston, just about an hour from Rayburn, he’d never set out specifically to become a full-time bass pro. He’d been a rodeo bull rider, but after he “got busted up,” that path became closed off. He began fishing B.A.S.S. tournaments in 1980, and at one early tournament, he recalled, he was “in the right place at the right time” and got paired up with Bill Dance, who in turn introduced him to Strike King’s Charles Spence. Spence asked him which circuits he was fishing and offered to pay his entry fees going forward if he’d fish B.A.S.S. consistently. “I just loved going out and chasing fish,” Dearman said. “But he pushed me to compete.”

Dearman’s early years at B.A.S.S. were marked by periods of success – he earned three Classic berths in the 1980s – but he couldn’t get over the hump to win a Bassmaster tournament. The closest he came was on his home waters of Lake Livingston in March of 1989, when Texas transplant Gary Klein overtook him on Day 3 to win by a little more than a pound. Prior to 1993, though, Dearman stumbled onto another bit of good luck that helped him earn his first win.

“I went down to the coast and fished with Terry Oldham,” he said, referring to a fellow Texas angler and tackle manufacturer. “He had some sort of braid on a spinning rod. It was competition kite string, really. He got it from guys who were shooting carp and gar and rough fish with it. I fished one other tournament before Rayburn. When we got there, the water was high up in the bushes. Everything was set up great.”

“The second day I drew Shaw Grigsby. He said he only needed to catch about 10 pounds to get in the Classic. I had a spot where just about every throw you’d catch one, but they were all just 2 pounds. By 2 o’clock I had 20 pounds. Shaw told me I needed to color the line (which was white). He also pointed out that I had a knot in my line about a foot above the jig and told me I needed to retie. I didn’t see the need to retie. With that original stuff I don’t know if I ever broke a fish off.”

Dearman’s catch of 67 pounds and 13 ounces set a record for a three-day, five-fish catch, but it also set off an arms race in the fishing line industry. Now, for the first time, anglers had access to line that had the strength of 80-pound test, but the diameter and limpness of 25-pound test. Don Wirth pointed out in the June 1993 issue of Bassmaster Magazine that other anglers had been using it, but that with Dearman’s $35,000 victory “the lid blew off one of the most hushed-up new product developments in fishing history.”

Lynch Line was marketed by Oldham and a partner with Dearman’s face on the package, but by the end of 1993 over a dozen other manufacturers entered the market with Kevlar or Spectra lines. Soon the market was flooded and the secret was out.

“It was hard to fight off the big guys,” Dearman recalled, and eventually Lynch Line was a thing of the past. Nevertheless, while he uses a variety of brands of braid today, he said that Sufix is the one he turns to most often because “it’s really, really round and smooth” like the original that he used in ‘93.

He said that nearly from the beginning he used braid in many circumstances where others would not, such as deep cranking, and he continues to be a believer in braid’s effectiveness despite others’ claims that it’s too visible or too noisy for many applications.

“For a lot of people it’s mental,” he said. “Bass are curious.” Nevertheless, just as in 1993, Dearman is not one to ignore a new product that is more suitable to the task at hand, and was quick to embrace fluorocarbon when it penetrated the American market.

After his win at Rayburn, Dearman continued to fish the Bassmaster Tour through 2005, and Open events through 2008, earning nine more top 10 finishes, including a runner-up spot at Rayburn in 1995 and a fourth-place finish there in 1996. At the dawn of the Elite Series, however, he elected to forego the berth he’d earned and became a landman in Arkansas, working in the oil and gas exploration industry with two-time Megabucks winner Doug Garrett. Later, fellow Rayburn hammer David Wharton joined them. Dearman pursued that path for more than a decade and then headed back to Texas. His son Slade, who fished 59 B.A.S.S. events, the last of them a 14th-place finish at Rayburn in 2004, now works for the railroad.

A few years ago, Dearman returned to Texas nearly full-time, except for the months of December and January which he largely spends hunting in Mexico. When he’s at home he guides for crappie at Sam Rayburn, as does fellow Texas legend Harold Allen. Just like Allen, who with a partner recently weighed in a 30-pound limit on Big Sam, Dearman can still be competitive. In June of 2015, he and partner Brian Branum won the First Annual Texas Shootout, presented by Bass Champs, on Rayburn and with it a $50,000 check.

“I still cherry pick a few events here and there,” he said. “I haven’t quit altogether. I’m not scared of nobody.”

So when he looks at the competitive landscape today, and sees Rick Clunn, who is just a few days short of a year older than Dearman, does it inspire him to get back out there?

“I miss it, I really do,” he said. “The competition and the camaraderie. But it’s a totally different breed of people who fish now. There are things they do a lot better than me. They’re great with electronics, and I take my hat off to them for that. They can find stuff in a half a day that would’ve taken us two weeks to find. I just hope that they remember that the people in my era who paved the way for them to make a living at it.”